Danny Treacy is familiar in borderlands, and he has always practised the aesthetic de-construction of those conceptual polarities in which our culture is imprisoned. He is like a blade runner, moving on the ridge where opposites touch each other, and sometimes they melt in order to create new, unknown and enlightening archipelagoes of sense. In his first series Fertile Ground, he presents obelisk structures, and their phallic symbology is smoothed down by a soft and smudgy visual treatment, which ascribes his work to feminine phenomenology.

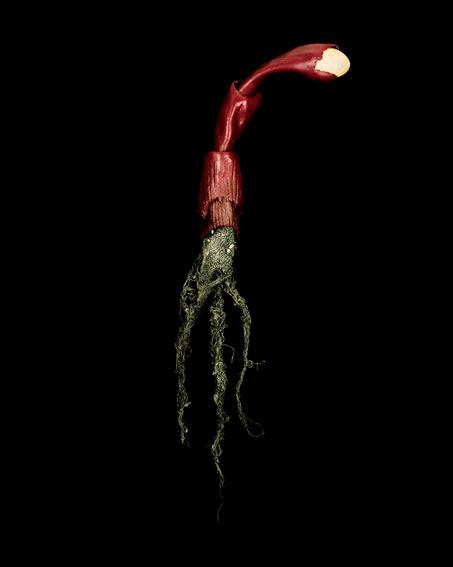

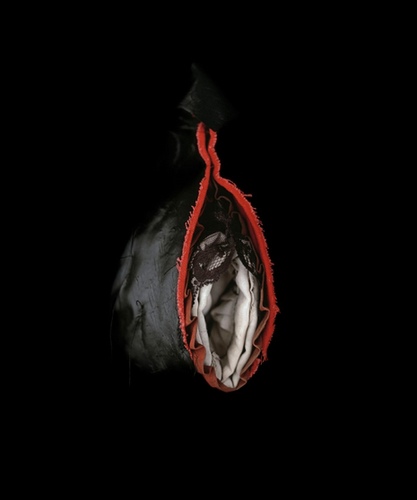

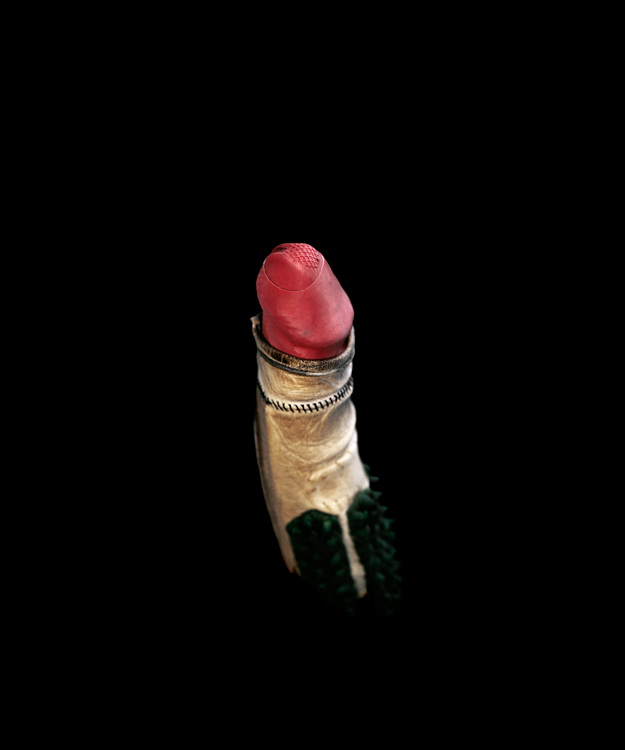

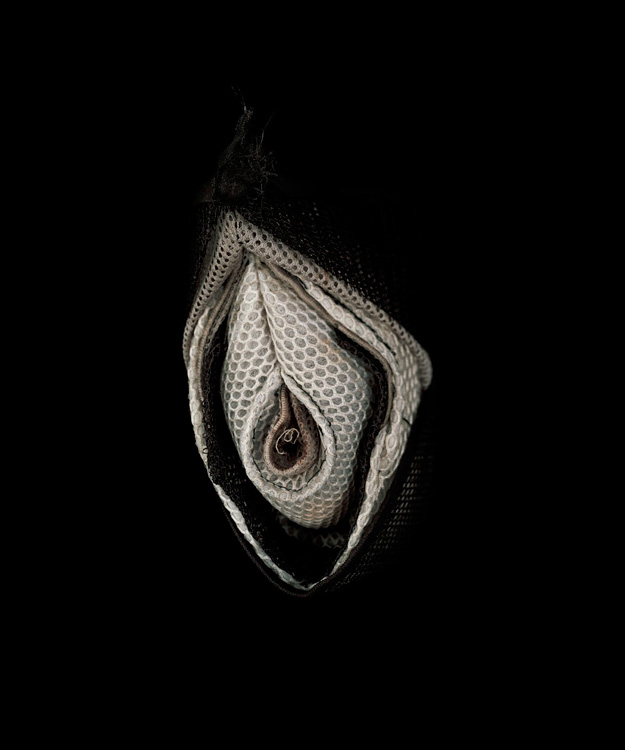

Danny Treacy is familiar in borderlands, and he has always practised the aesthetic de-construction of those conceptual polarities in which our culture is imprisoned. He is like a blade runner, moving on the ridge where opposites touch each other, and sometimes they melt in order to create new, unknown and enlightening archipelagoes of sense. In his first series Fertile Ground, he presents obelisk structures, and their phallic symbology is smoothed down by a soft and smudgy visual treatment, which ascribes his work to feminine phenomenology.  In Those Treacy permeates the organic with the inorganic, presenting the portal organs between the inside and the outside, genitals – which come out from the body or create inlets in it – set up as assemblages of textile materials.

In Those Treacy permeates the organic with the inorganic, presenting the portal organs between the inside and the outside, genitals – which come out from the body or create inlets in it – set up as assemblages of textile materials.

Everything with a virtuosity which reminds of Arcimboldo. Swollen black masses with red almond-shaped yarns inscribed, crowned by laces in correspondence of the clitoris region, a rampant penis with red-rubber prepuce sewed to a stem of shiny white leather, open up oysters of blue latex, sweetly resting jeans-phallus.

Everything with a virtuosity which reminds of Arcimboldo. Swollen black masses with red almond-shaped yarns inscribed, crowned by laces in correspondence of the clitoris region, a rampant penis with red-rubber prepuce sewed to a stem of shiny white leather, open up oysters of blue latex, sweetly resting jeans-phallus.

In this way the reification of body jewels is diluted in a playful and desublimating irony.

In this way the reification of body jewels is diluted in a playful and desublimating irony.

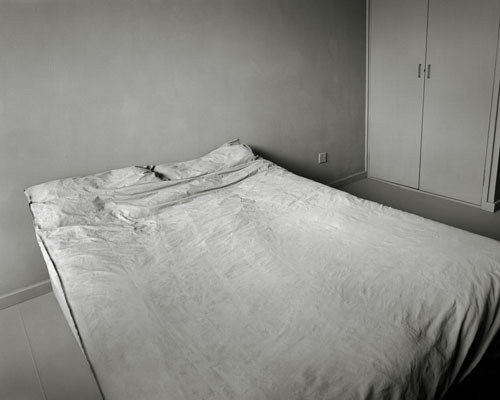

The Grey area series is set up by environmental photographs. Piles of hospital chairs, lockers, steep landings, creased beds, all depicted after being entirely painted in light grey, as if they have been covered by radioactive fall-out dust. Chromatic homogeneity infuses to the viewer the idea of an aseptic space, but also dusty, dirty and dreary at the same time. The sense of void fuses with claustrophobia, the absence of human figures evokes the spectre of their presence. in the author’s intentions, a deeply erotic spectre.

The Grey area series is set up by environmental photographs. Piles of hospital chairs, lockers, steep landings, creased beds, all depicted after being entirely painted in light grey, as if they have been covered by radioactive fall-out dust. Chromatic homogeneity infuses to the viewer the idea of an aseptic space, but also dusty, dirty and dreary at the same time. The sense of void fuses with claustrophobia, the absence of human figures evokes the spectre of their presence. in the author’s intentions, a deeply erotic spectre.

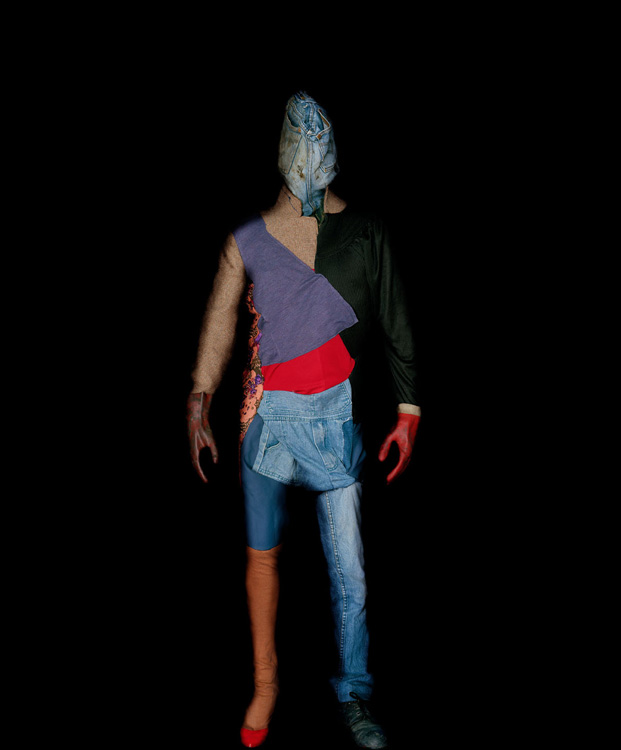

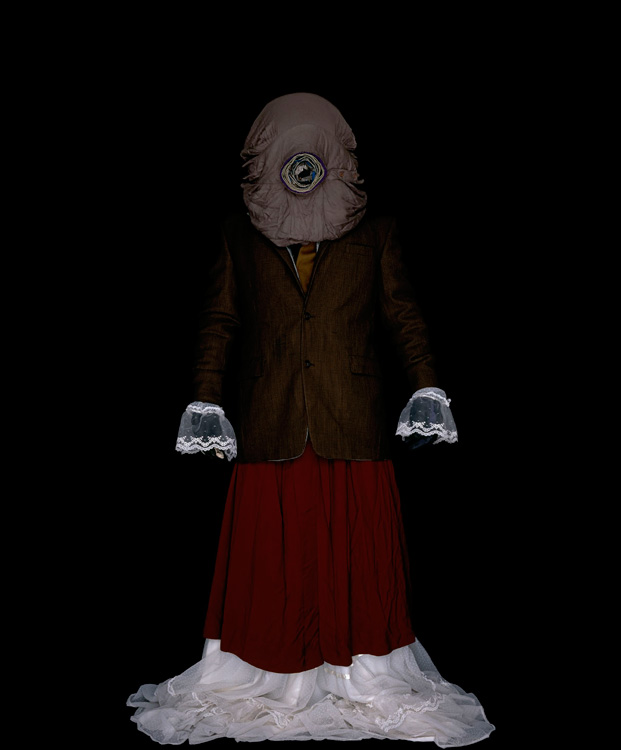

But let us consider the last series Them. Besides the usual balance on the slash which separates antithetical couples, Treacy asks questions about fashion as a system of enhancing signs, about its shadow double of anti-glamour disvalue, and about the parallel universe of Alterity, in all its social meanings. Big-size photos, in which human figures emerge from a very black background, all faceless, all composed by pieces of clothes, searched in woods and parcking places, absurdly put together with thread and needle. The fact that it is always Treacy who wears these clothes is a fundamental stage of the poetic process: the author unsettles his own individual self, getting lost in the selves of former owners. The Other he depicts can be inferred by the structural opposition with the metaphysical subjetc par excellence, of Platonic-Cartesian provenance, male, well-off, and heterosexual. With respect to him all the others are in the condition of objects. Them, direct objects. These categories of extraneousness spring one from another, by parthenogenesis. The first picture is a sexual hybrid. Number 1 is a hermaphrodite, dressed in the same way as those who used to exhibit themselves in freak shows during the Nineteenth Century, a red stiletto on one side, a male shoe on the other, with that refined oddity in look typical of homosexuals, and unwelcome to the exponents of normality. The same type of eccentricity for number 13, who is wearing a blue peacock shirt with golden inserts, a pair of strange glitter trousers, and a hood with an equivocal hole in the middle.

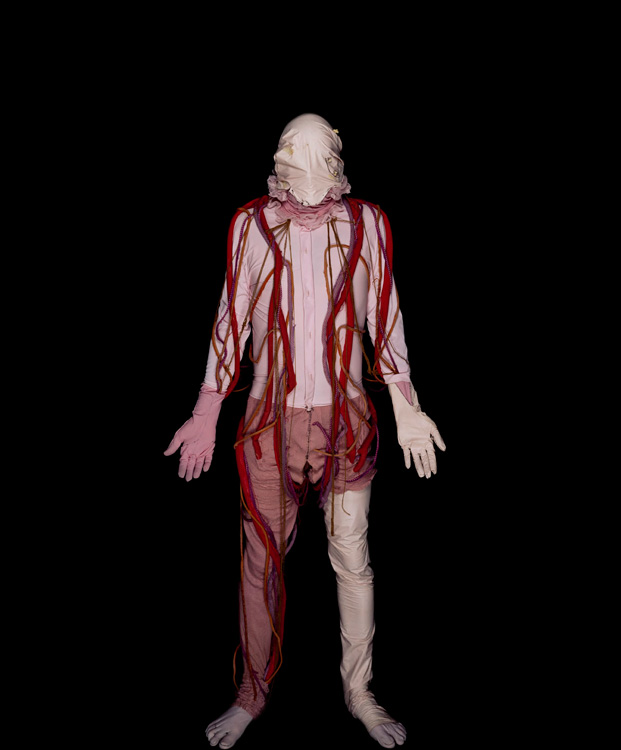

The same type of eccentricity for number 13, who is wearing a blue peacock shirt with golden inserts, a pair of strange glitter trousers, and a hood with an equivocal hole in the middle.  Also number 19 is enrolled in the queer category: a figure in pink, a male body with laces around his neck, with an open slit between his legs, as a fake, frayed vagina. Big fibrous hollows envelop him, as veins on a skinned figure. This stress on the anatomical structure could classify number 19 as a trans-gender creature.

Also number 19 is enrolled in the queer category: a figure in pink, a male body with laces around his neck, with an open slit between his legs, as a fake, frayed vagina. Big fibrous hollows envelop him, as veins on a skinned figure. This stress on the anatomical structure could classify number 19 as a trans-gender creature. Through transexuality from male to female we get to the next diverging class: women. The number 8 lady has synthetic laces around her hands, and a loose-fitting hood, with a liquefied eyeball in its middle. A mouth and a sexual orifice at the same time, it concentrates the three female penetration functions, and what Bataille considers the main vector of seduction, the eye.

Through transexuality from male to female we get to the next diverging class: women. The number 8 lady has synthetic laces around her hands, and a loose-fitting hood, with a liquefied eyeball in its middle. A mouth and a sexual orifice at the same time, it concentrates the three female penetration functions, and what Bataille considers the main vector of seduction, the eye. Besides number 2, with her awful desperate housewife skirt, we also have number 20, a ghost covered by an integral burqa. We can guess her disproportionate, monster-like shapes. Other two differential groups begin after her, huge, heavy, threatening.

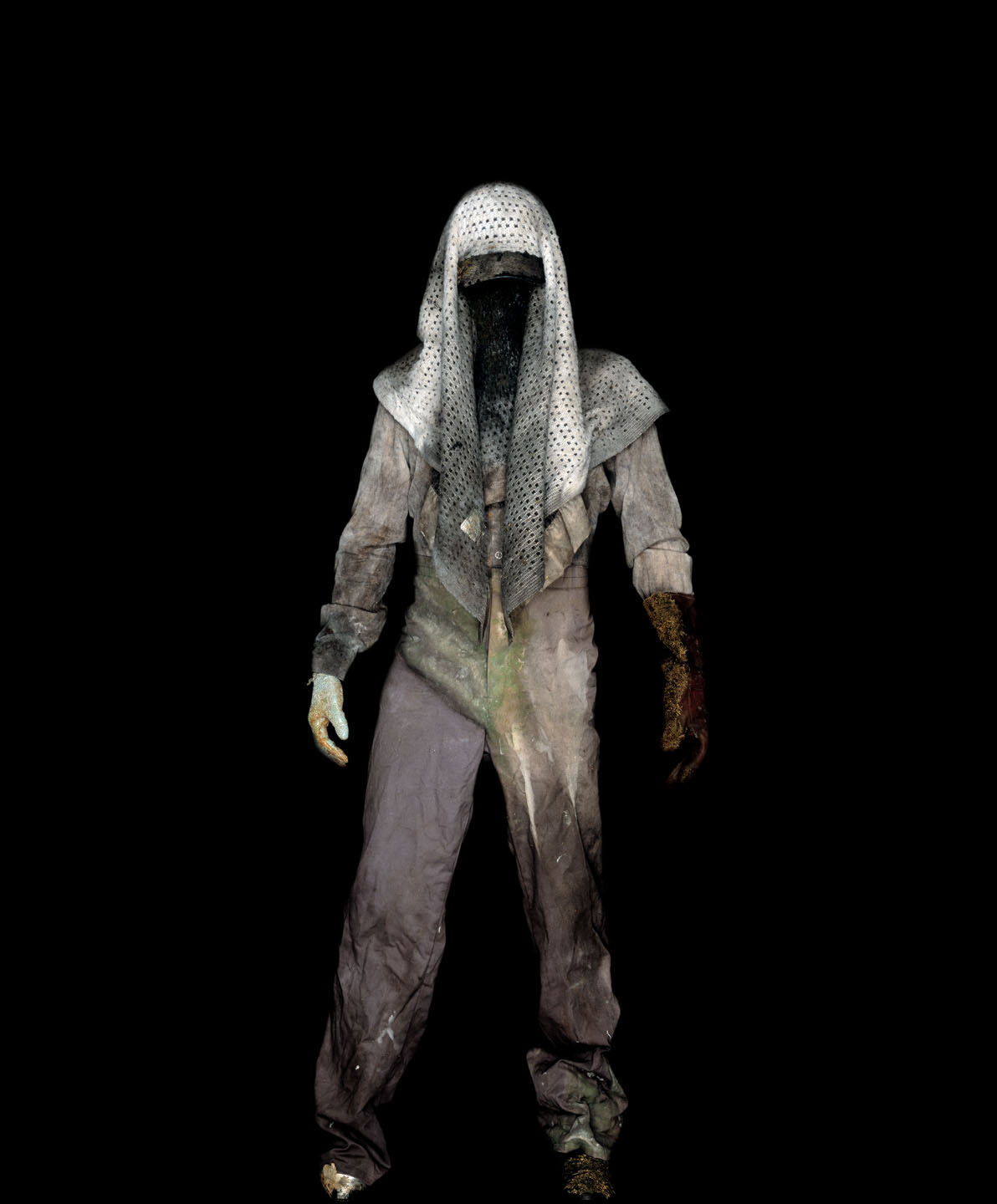

Besides number 2, with her awful desperate housewife skirt, we also have number 20, a ghost covered by an integral burqa. We can guess her disproportionate, monster-like shapes. Other two differential groups begin after her, huge, heavy, threatening. On one side, with the number 2 mujaheddin with his open-work kefiah, we have the barbarians, the xenoi, the islamic Umma. A colossus, perceived indistinctly by the Western world as a lair of terrorists and crazy fanatics. Their cultural, political and social identity is stronger than ours.

On one side, with the number 2 mujaheddin with his open-work kefiah, we have the barbarians, the xenoi, the islamic Umma. A colossus, perceived indistinctly by the Western world as a lair of terrorists and crazy fanatics. Their cultural, political and social identity is stronger than ours.  But this woman covered as a phantom and socially buried alive is also related with the dead. Rational Modernity has broken it off with them, repressing all kind of symbolic exchanges with them, relegating them in a limbo of non-existence. Also the enigmatic number 17, with his brown habit/sarcophagus, seems to belong to this class, and also to the class of soldiers, for the red target on his mask.

But this woman covered as a phantom and socially buried alive is also related with the dead. Rational Modernity has broken it off with them, repressing all kind of symbolic exchanges with them, relegating them in a limbo of non-existence. Also the enigmatic number 17, with his brown habit/sarcophagus, seems to belong to this class, and also to the class of soldiers, for the red target on his mask. The soldiers represent the turbulent faction of the others, hostile enemies, in which we can put the mujaheddin, the number 4 – a figure with an armour and a sort of sock hanging from his pants – and the number 18 worker/soldier, all black, with a medieval helmet and huge working-boots.

The soldiers represent the turbulent faction of the others, hostile enemies, in which we can put the mujaheddin, the number 4 – a figure with an armour and a sort of sock hanging from his pants – and the number 18 worker/soldier, all black, with a medieval helmet and huge working-boots.  Since the first world conflict a deep connection has been established between the warcraft and the conditions of the industrial trade.

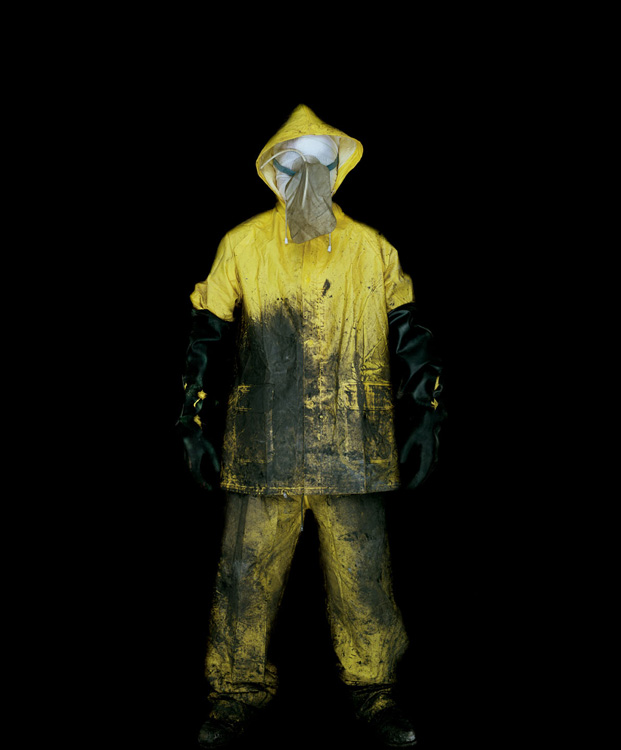

Since the first world conflict a deep connection has been established between the warcraft and the conditions of the industrial trade.  Work is serial, painful, mechanized, inhuman as trench life. We have the dirty yellow dustman (number 5), who speaks about men at work, fishing boats, rain and concrete, number seven’s white overalls against radiations, the deep mad streak of number 10’s white coat, with his hands shut within pipe-gloves, as a mad doctor unable to use his limbs. Madness, another continental prison for outsiders, joins 10 with 16, a horrible tramp, a patchwork of filthy and burned fabrics.

Work is serial, painful, mechanized, inhuman as trench life. We have the dirty yellow dustman (number 5), who speaks about men at work, fishing boats, rain and concrete, number seven’s white overalls against radiations, the deep mad streak of number 10’s white coat, with his hands shut within pipe-gloves, as a mad doctor unable to use his limbs. Madness, another continental prison for outsiders, joins 10 with 16, a horrible tramp, a patchwork of filthy and burned fabrics.

The opposite pole to Man has been occupied by the Machine since contemporaneity started, instead of the Animal during the past centuries. Its negative polarity of instincts, violence and bestial irrationality, its physical features have become constitutive of the devil’s iconography.The chimerical creatures depicted by Treacy are a dog (number 11), the first animal domesticated by men, their best friend, suited to being maltreated and abandoned, and number 15, a frightening cross between the pig, the food victim par excellence, similar to its persecutor for its intelligence, skin grain, and organic compatibility, and the mouse, the only parasite able to survive to humans in the perspective of an atomic disaster.

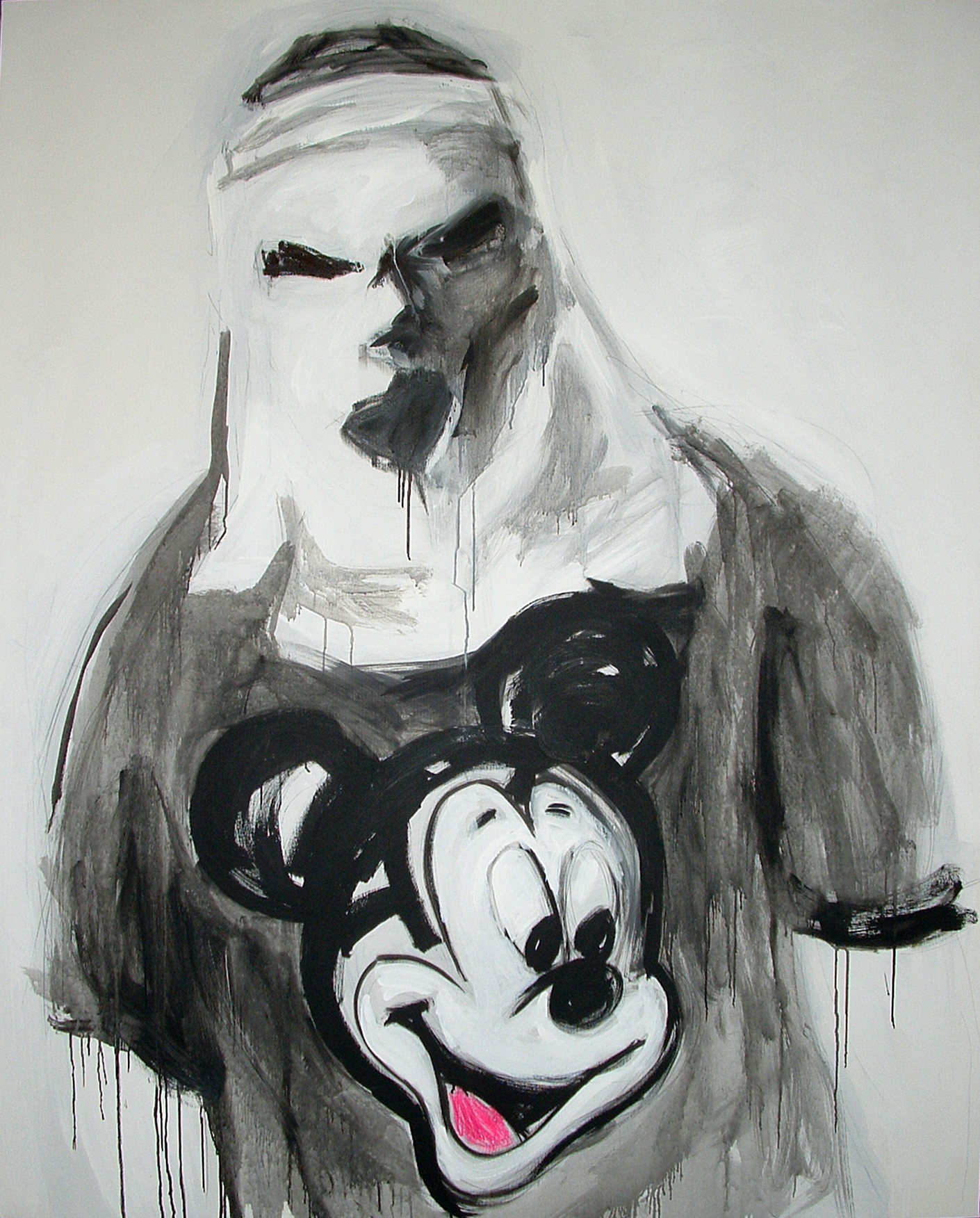

These typologies of dissonance towards the established order find a mirror image in the work Who is who, by the young artist Adriana Jebeleanu, a pictorial installation of political star-system icons. The most macroscopic trait which joins them is their facial deprivation. None of Tracey’s aliens has a face, they are all hooded, veiled, masked, hidden. This is functional to a typifyzation of the Other embodied by them. In Who is who, the characters depicted don’t need to have a face, they are perfectly recognizable even through an iconic representation, which accounts only for the outline of the subject and of some of its main features. Ratzinger has his face painted in black, Saddam with a trace of a moustache and eyebrows, Lady Diana with a light make-up shadow, Berlusconi with a disneyan huge smile. They have no face because they are portrayals of a radical alterity class, men of power, intimately disjointed from us, more than the unheimliche Them. And still many people love Diana, share the world-vision of the sovereign of Christianity, have saluted Arafat as a redemptor, believe in the uprightedness of Bush’s war. In spite of their distance from us, many people adopt an attitude of identification towards them, and feel represented by the political leadership. Princes, as the protagonists of Them, belong to a marginal category . All the ancient cultures which made human sacrifices chose their victims among minorities, to avoid intestine retaliations, and often even kings belonged to these. Lady D, the princess who died for a fame surplus, Is a perfect example. All the non-faces of Who is who are connected with the spheres of death, power and war.

In Who is who, the characters depicted don’t need to have a face, they are perfectly recognizable even through an iconic representation, which accounts only for the outline of the subject and of some of its main features. Ratzinger has his face painted in black, Saddam with a trace of a moustache and eyebrows, Lady Diana with a light make-up shadow, Berlusconi with a disneyan huge smile. They have no face because they are portrayals of a radical alterity class, men of power, intimately disjointed from us, more than the unheimliche Them. And still many people love Diana, share the world-vision of the sovereign of Christianity, have saluted Arafat as a redemptor, believe in the uprightedness of Bush’s war. In spite of their distance from us, many people adopt an attitude of identification towards them, and feel represented by the political leadership. Princes, as the protagonists of Them, belong to a marginal category . All the ancient cultures which made human sacrifices chose their victims among minorities, to avoid intestine retaliations, and often even kings belonged to these. Lady D, the princess who died for a fame surplus, Is a perfect example. All the non-faces of Who is who are connected with the spheres of death, power and war.

War is an obsessively recurring theme in Jebe’s work. She comes from Romania, and when she was fourteen she witnessed the fall of the regime, she remembers the catastrophic clamour of weapons, and the tank tracks in streets.

War is an obsessively recurring theme in Jebe’s work. She comes from Romania, and when she was fourteen she witnessed the fall of the regime, she remembers the catastrophic clamour of weapons, and the tank tracks in streets.  In the series Romania Calling, beside china cups and flowery kimonos, there are four impressive triptychs of machineguns, knives, revolvers. In War Game there are monumental war machines represented, titled with frivolous, bitter and disquieting expressions.

In the series Romania Calling, beside china cups and flowery kimonos, there are four impressive triptychs of machineguns, knives, revolvers. In War Game there are monumental war machines represented, titled with frivolous, bitter and disquieting expressions.  A foggy wall of barbedwire is called Potential Freedom, an aircraft carrier is a Dancer in the Dark, a tank becomes the Lamb of God, another one carries us to the Vanity Fair.

A foggy wall of barbedwire is called Potential Freedom, an aircraft carrier is a Dancer in the Dark, a tank becomes the Lamb of God, another one carries us to the Vanity Fair.  To this deadly fair also belong the Jihad soldiers of Who is who, they wear t-shirts with Mickey Mouse and the Pink Panther and designer clothes, like the disturbing madonna with veil, Kalashnikov and Nike logo.

To this deadly fair also belong the Jihad soldiers of Who is who, they wear t-shirts with Mickey Mouse and the Pink Panther and designer clothes, like the disturbing madonna with veil, Kalashnikov and Nike logo.

The political organizations which patronize suicidal attacks are definitely multinational corporations, and the martyrdom for an ideological and religious cause is a trend in conflict areas. And a deviated fashion is central also in the work of Treacy.Treacy transforms himself in Them and poses for the pictures, Jebe confirms that all her works are self-portaits, and that their face uprooting is functional to self-substitution. The viewer changes in what he sees. The Identities of the viewer, the artist and the subject combine.We become the others.

Published on Inside Magazine 18, summer 2008. download pdf