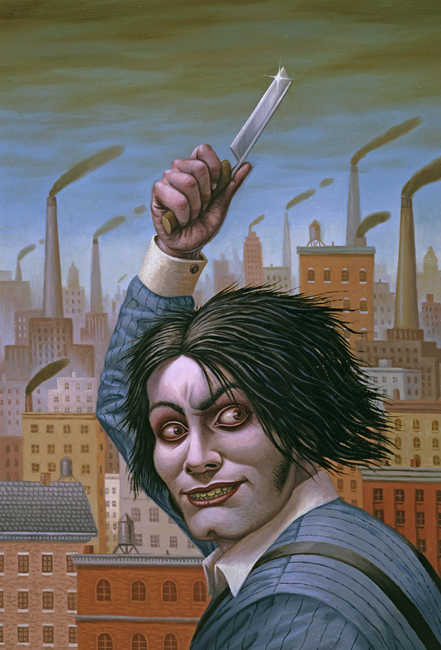

You raise the blade, you make the change You re-arrange me till I’m sane.

Here’s someone in my head but it’s not me.

And if the cloud bursts, thunder in your ear, you shout and no one seems to hear

and if the band you’re in starts playing different tunes

I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon

Pink Floyd

These are my friends, see how they glisten

Sweeney Todd

A beach with a refinery on the back, and the sky with a constellation of Sanyo, Good Year, Direct Tv’s airships. Everything one may need to receive electromagnetic signals, to move, to watch, to desire, to live unreal lives in a pre-recorded broadcast. There are tourists in the foreshore, and a blonde teenager in the foreground, with huge eyes, an ice-cream full of milk and sugar, and a mobile-phone. The girl is wearing a t-shirt with the prism of The Dark Side of the Moon, the Pink Floyd’s concept album about death, fear of flying, and madness as a rift between man and his environment. A bee, the symbol of language in the Jewish iconology, is flying towards her.

A beach with a refinery on the back, and the sky with a constellation of Sanyo, Good Year, Direct Tv’s airships. Everything one may need to receive electromagnetic signals, to move, to watch, to desire, to live unreal lives in a pre-recorded broadcast. There are tourists in the foreshore, and a blonde teenager in the foreground, with huge eyes, an ice-cream full of milk and sugar, and a mobile-phone. The girl is wearing a t-shirt with the prism of The Dark Side of the Moon, the Pink Floyd’s concept album about death, fear of flying, and madness as a rift between man and his environment. A bee, the symbol of language in the Jewish iconology, is flying towards her.

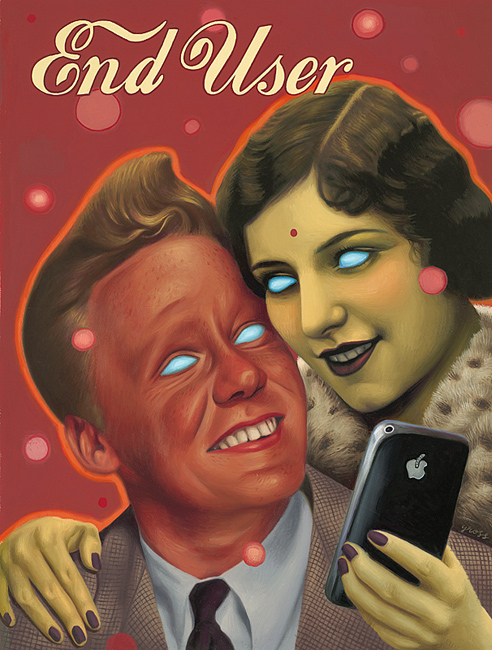

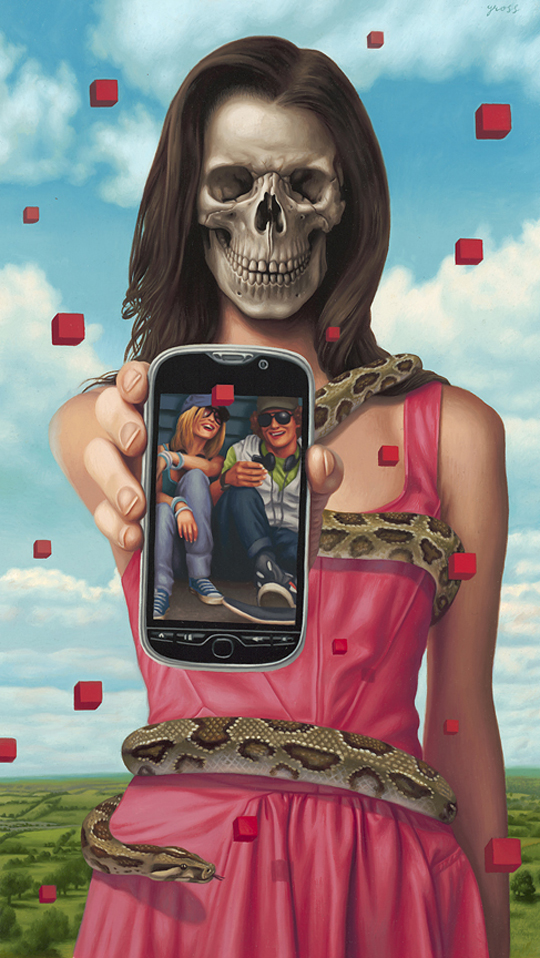

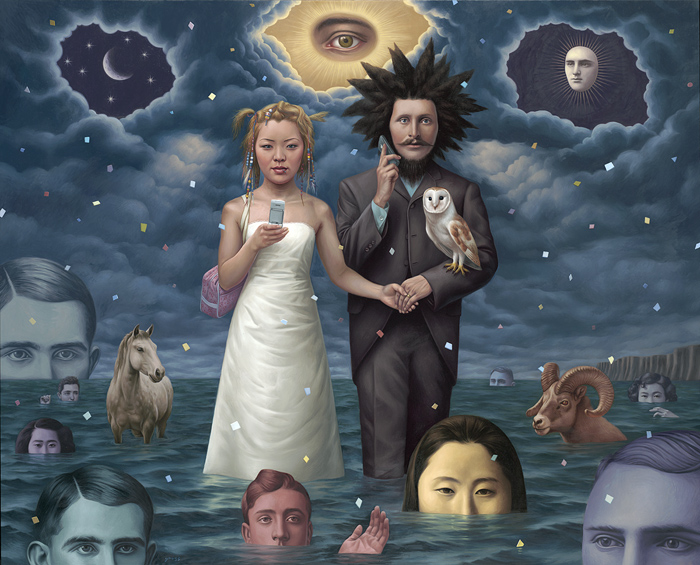

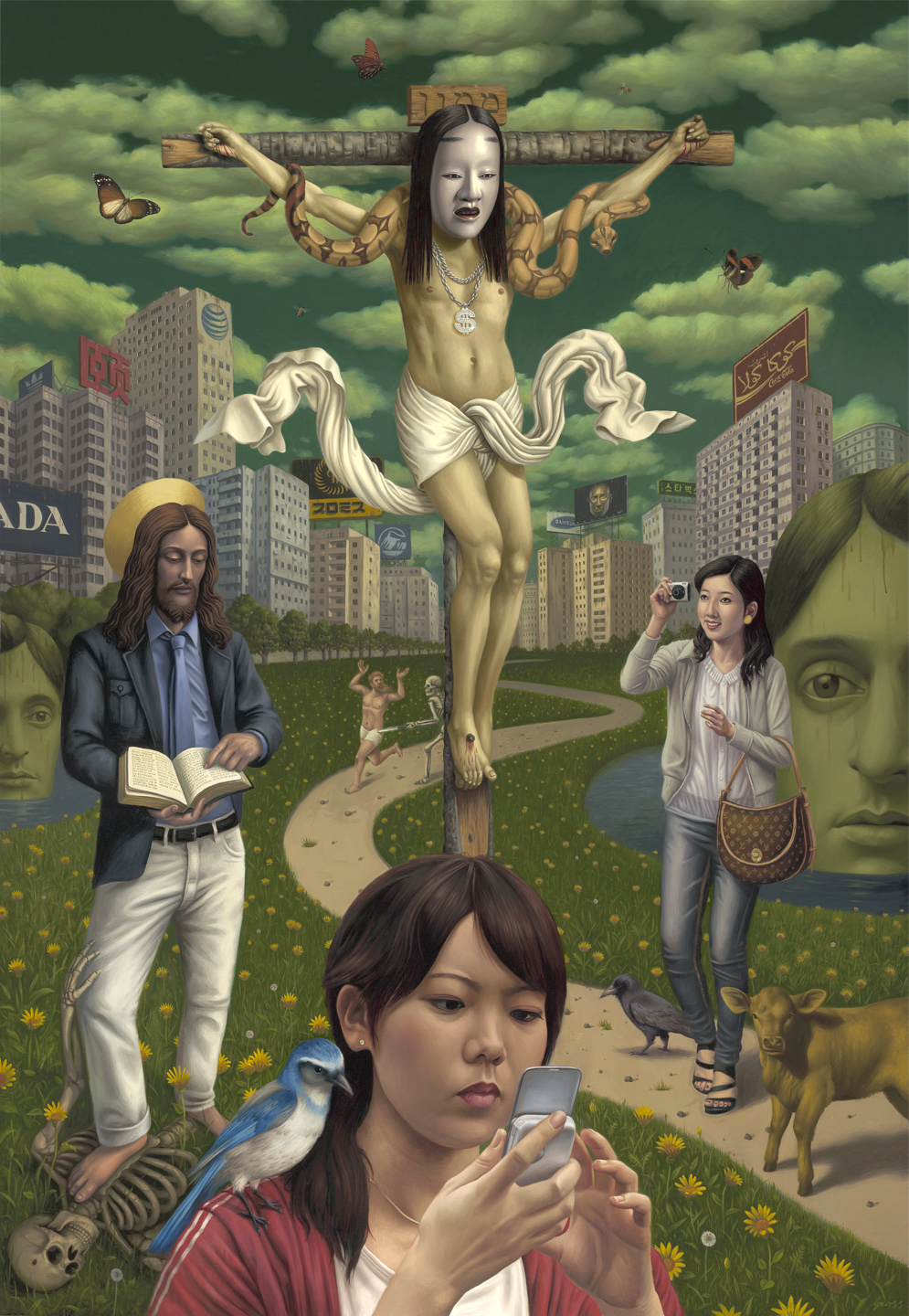

The cell-phone recurs in many works of Alex Gross.

The cell-phone recurs in many works of Alex Gross.

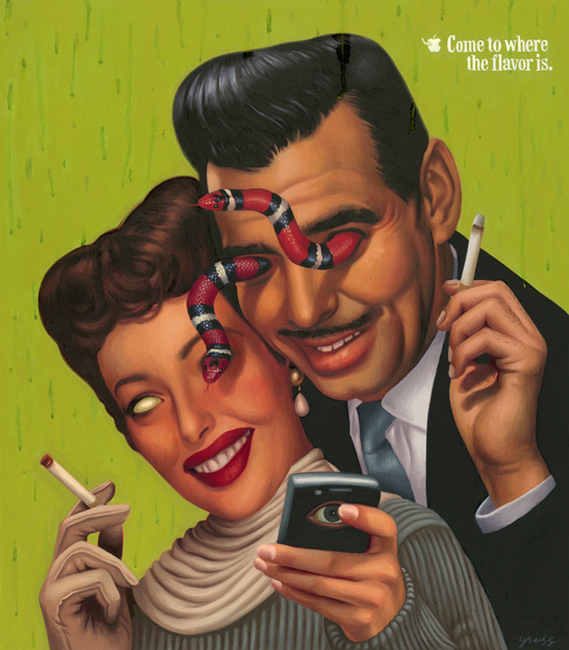

A shell of the world of its possessors, a social object par excellence, a new medium in the history of writing and inscriptions, the mobile is emblematic of the dislocation of man’s presence. But in many works of Gross (Come Where the Flavour Is, Dark Side, End User, Kool Aid Drinkers, Mammon, Obedience, Signals, Wish You Where Here) the cell-phone often has disquieting meanings: negation of the presence, absence, actual loneliness.

A shell of the world of its possessors, a social object par excellence, a new medium in the history of writing and inscriptions, the mobile is emblematic of the dislocation of man’s presence. But in many works of Gross (Come Where the Flavour Is, Dark Side, End User, Kool Aid Drinkers, Mammon, Obedience, Signals, Wish You Where Here) the cell-phone often has disquieting meanings: negation of the presence, absence, actual loneliness.

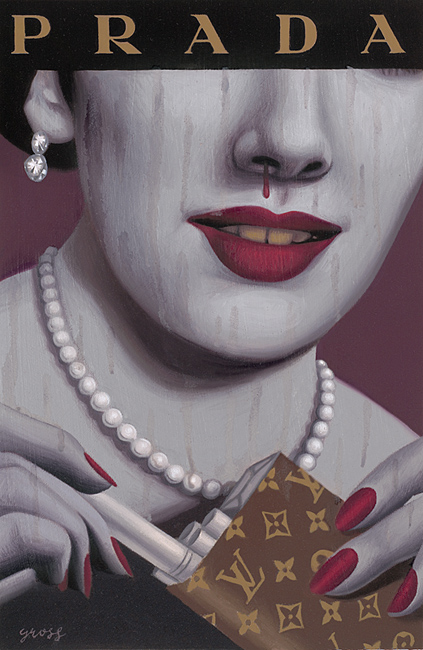

Other frequent elements are Japanese women.

Other frequent elements are Japanese women.

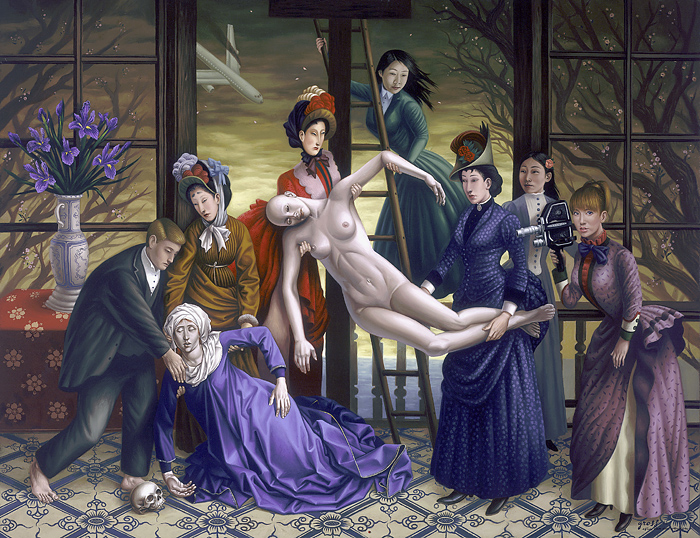

Variously dislocated on the time-line, they might be pin-ups of the Forties and Fifties, red-cross nurses or Victorian ladies, geisha-girls with kimonos. The feminine imaginary of Japan (which the artist knows perfectly thanks to a research on the field, and the consequent publication of the book Japanese Beauties for Taschen) conveys an enigmatic kind of beauty, often incomprehensible to the Western view.

Variously dislocated on the time-line, they might be pin-ups of the Forties and Fifties, red-cross nurses or Victorian ladies, geisha-girls with kimonos. The feminine imaginary of Japan (which the artist knows perfectly thanks to a research on the field, and the consequent publication of the book Japanese Beauties for Taschen) conveys an enigmatic kind of beauty, often incomprehensible to the Western view.

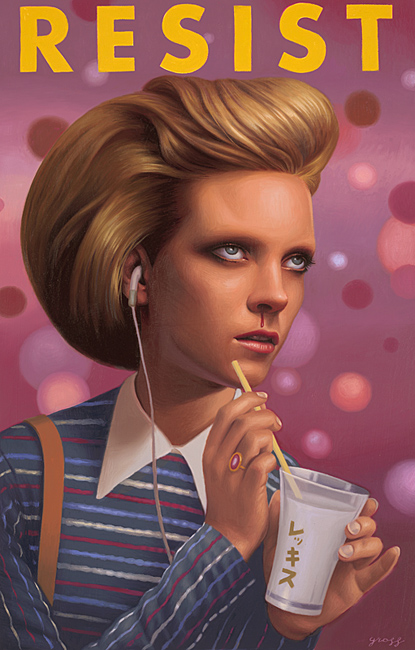

The Japanese women of Gross belong to the floating w, to bijin-ga (the Eighteenth Century advertisements for the courtesans of the red light district of Yoshiwara), but also to a contemporaneity made of designer clothes, blonde highlights and tattoos. Bijin-ga has actually constituted the dawn of fashion advertising in Japan. Alex Gross represents a cadaverous geisha girl with epistaxis to promote the cigarettes by Prada, wrapped in a pattern with Louis Vuitton’s logo.

The Japanese women of Gross belong to the floating w, to bijin-ga (the Eighteenth Century advertisements for the courtesans of the red light district of Yoshiwara), but also to a contemporaneity made of designer clothes, blonde highlights and tattoos. Bijin-ga has actually constituted the dawn of fashion advertising in Japan. Alex Gross represents a cadaverous geisha girl with epistaxis to promote the cigarettes by Prada, wrapped in a pattern with Louis Vuitton’s logo.

This deconstruction of the advertising artifices, this revealing of their uncanny side, constitutes one of the most interesting aspects of Gross’ poetics.

This deconstruction of the advertising artifices, this revealing of their uncanny side, constitutes one of the most interesting aspects of Gross’ poetics.

The long haired lady in the Starbucks’ icon has a skull instead of her face, such as one of the teenager riding a pink Lambretta in the bucolic nightmare of Premonition, maybe an omen of a deadly crash.

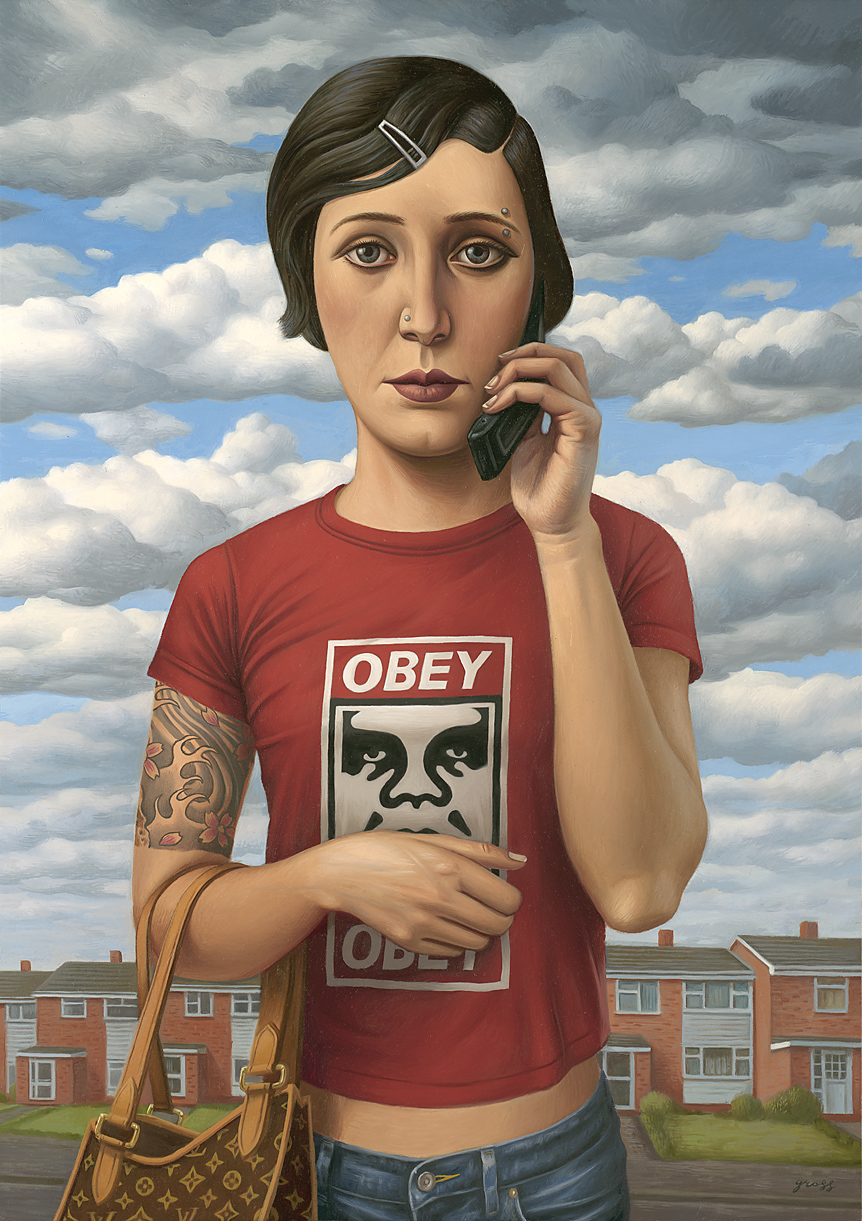

A melancholic girl, not so much beautiful, but surely very cool, according to her piercing, her tattoo, her Louis Vuitton bag, her Shepard Failey T-shirt, becomes the allegory of conformism in Obedience. Because the imperative to coolness, from a rebel feature, has become a paradoxical script to which obey.  Alex Gross marries the historical Surrealism’s ingredients, such as pneumatic vacuum, animal symbology, a mix of different temporalities (which probably start with 1435 and the deposition of Rogier Van Der Weyden) to the distinctive elements of pop culture.

Alex Gross marries the historical Surrealism’s ingredients, such as pneumatic vacuum, animal symbology, a mix of different temporalities (which probably start with 1435 and the deposition of Rogier Van Der Weyden) to the distinctive elements of pop culture.  For instance, the flying devices: aeroplanes, airships, vectors of travelling, of territorial dominium on a large scale, of speed and advertising. They would have been solved by doctor Freud as trivial phallic symbols, according to his The Interpretation of Dreams.

For instance, the flying devices: aeroplanes, airships, vectors of travelling, of territorial dominium on a large scale, of speed and advertising. They would have been solved by doctor Freud as trivial phallic symbols, according to his The Interpretation of Dreams.

Other pop culture topoi are the Forties an Fifties, quoted in hairstyles and atmospheres. The years which brought from the great destruction to the great dream, the years of endless abundance, of the boom of the cultural industry, of the omnipotence of movie stars. The Fifties saw the birth of Playboy, the Californian mythology, and rock ‘n roll. But they were also the years of lobotomies, of McCarthy’s witch hunt, of the conformism at any cost.

Other pop culture topoi are the Forties an Fifties, quoted in hairstyles and atmospheres. The years which brought from the great destruction to the great dream, the years of endless abundance, of the boom of the cultural industry, of the omnipotence of movie stars. The Fifties saw the birth of Playboy, the Californian mythology, and rock ‘n roll. But they were also the years of lobotomies, of McCarthy’s witch hunt, of the conformism at any cost.

Alex Gross often represents the post-modern illness, as a disease with many symptoms. It empties the eyes of the people, explodes in sudden haemorrhages, makes addict of cigarettes and sugar-blues dishes. A syndrome beyond cure, which separates people one from another by a solipsistic trance with their electronic devices. The only antidote to this sickness is to make an involution of the paradigm, meeting (or becoming) a modern monster like Sweeney Todd. Serial killer barber, who really existed in the London of the industrial revolution, Todd cut the throats of his clients to robe them of their money, in cahoots with his lover, who later recycled the corpses in her delicious meat pie, for sale in the back lane of Bell Yard. In short, the apotheosis of work ethic.

Alex Gross often represents the post-modern illness, as a disease with many symptoms. It empties the eyes of the people, explodes in sudden haemorrhages, makes addict of cigarettes and sugar-blues dishes. A syndrome beyond cure, which separates people one from another by a solipsistic trance with their electronic devices. The only antidote to this sickness is to make an involution of the paradigm, meeting (or becoming) a modern monster like Sweeney Todd. Serial killer barber, who really existed in the London of the industrial revolution, Todd cut the throats of his clients to robe them of their money, in cahoots with his lover, who later recycled the corpses in her delicious meat pie, for sale in the back lane of Bell Yard. In short, the apotheosis of work ethic.

The same ethic of Mammon, the work dedicated to the god of avarice. Jesus has transformed into a casual-dressed student, who abdicates from his place on the cross, to a hybrid with male body and Onna mask from Japanese Noh theatre. Around the crucifixion scene, there are tourists busy writing txt and taking pictures. The new messiah has the dollar sign around his neck, and is surrounded by giant corporation signs.

Alex Gross associates dreaming modalities, full of mystery and grace, with a look as sharp as a blade, which focuses on neurosis, vices and angst of men in the empire of global communication.

Alex Gross associates dreaming modalities, full of mystery and grace, with a look as sharp as a blade, which focuses on neurosis, vices and angst of men in the empire of global communication.  But, most of all, the loneliness of the ones who got lost in a world of ghosts.

But, most of all, the loneliness of the ones who got lost in a world of ghosts.

published on Lobodilattice 1/17/2011