According to the ancient Japanese system of time measurement,the eighth hour, yatsudoki, corresponded to our 2 after midnight.

Each Japanese hour was equal to two European hours,so there were only six hours instead of twelve:

these six hours were counted backwards, i.e. 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4 …

So the ninth hour corresponded to our midday or midnight,the half past eight was our one o’clock,

eight o’clock was our two o’clock.Two after midnight, called also the hour of the ox,was the Japanese hour of spirits and ghosts.

Hugo Von Hofmannsthal

Eight million deities exist in the world, and we are constantly surrounded by spirits.

According to Shinto, the animist religion of Prehistoric Japan, the human beings, after death, go to a parallel reality, coexistent with our dimension, taking the form of ghosts, gods or other entities. If the rituals of purification of the deceased are not made in strict accordance with the rules, the dead transform into yuurei, which are ghosts confined in the place they lived. The yuurei is a creature completely absorbed by a desire: it can be exorcised only after its desire has been fulfilled. In the land of the Rising Sun, the shadows are mostly of female gender and, unlike the occidental setting -which prefers the winter-frost- they usually show up in the summer heat. Demons with a long neck, oni with great claws, mischievous tengu with bird heads, stupefying yukai, the Japanese after-world is unsettled, changeable, shifting, eclectic. Its ghosts are usually called bakemono, which means “thing that transforms itself”. Katsushika Hokusai has often represented rokurokubi, vampire-women with a neck which can extend for many metres.

In the land of the Rising Sun, the shadows are mostly of female gender and, unlike the occidental setting -which prefers the winter-frost- they usually show up in the summer heat. Demons with a long neck, oni with great claws, mischievous tengu with bird heads, stupefying yukai, the Japanese after-world is unsettled, changeable, shifting, eclectic. Its ghosts are usually called bakemono, which means “thing that transforms itself”. Katsushika Hokusai has often represented rokurokubi, vampire-women with a neck which can extend for many metres.

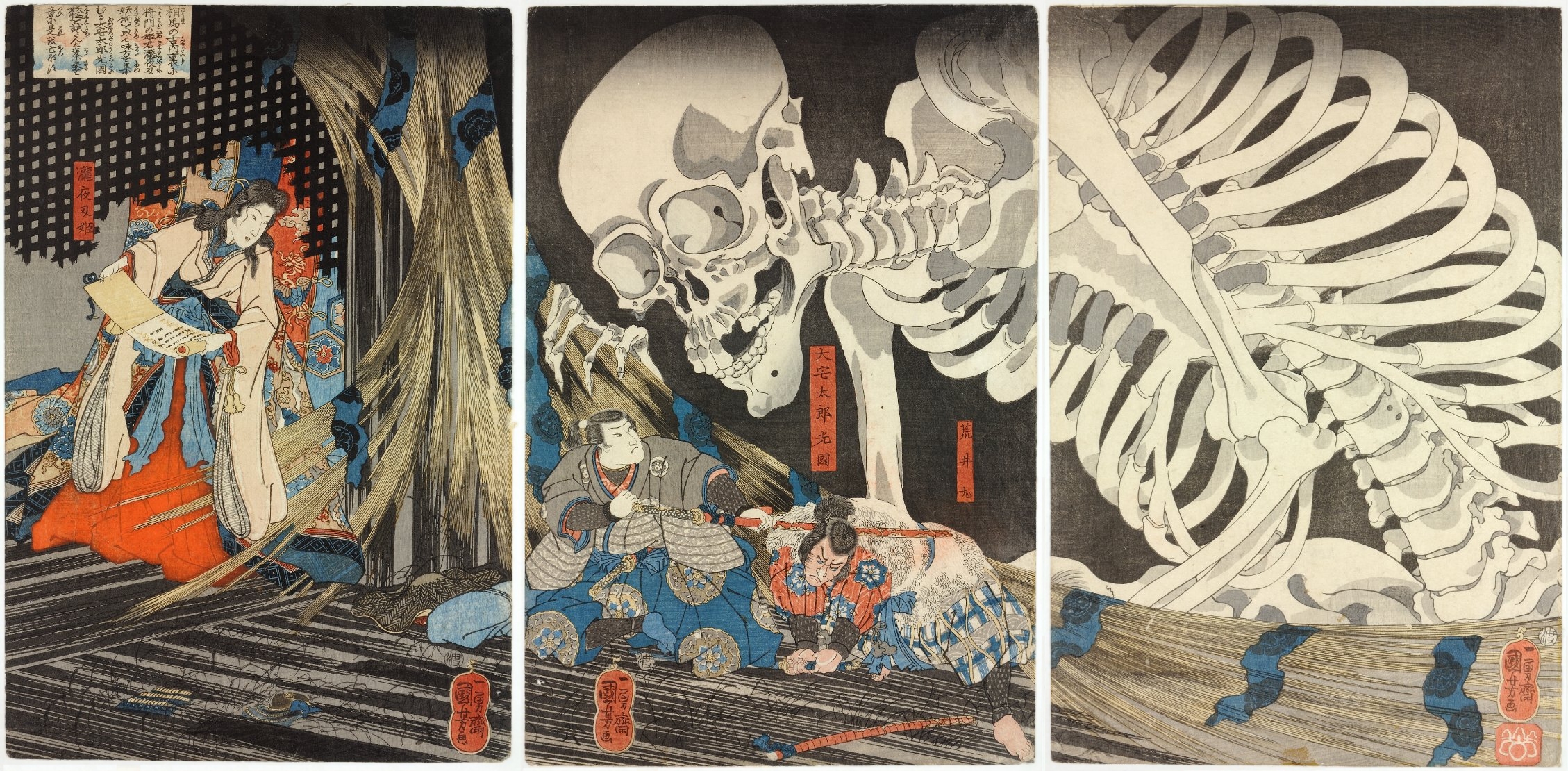

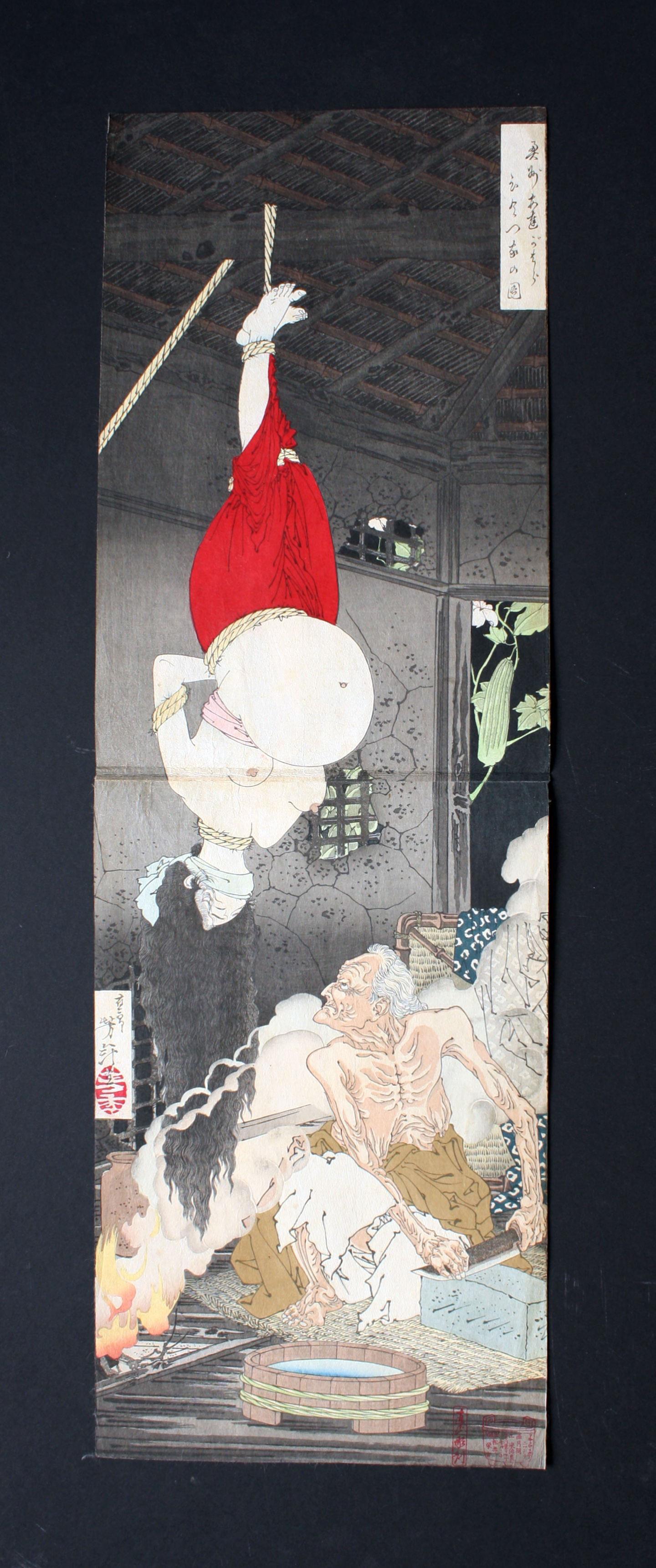

The Nineteenth Century artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi – who achieved success after contaminating the floating world with extremely elegant images of blood and torture- dedicates a series of prints to thirty-six famous ghost stories.

The Nineteenth Century artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi – who achieved success after contaminating the floating world with extremely elegant images of blood and torture- dedicates a series of prints to thirty-six famous ghost stories.

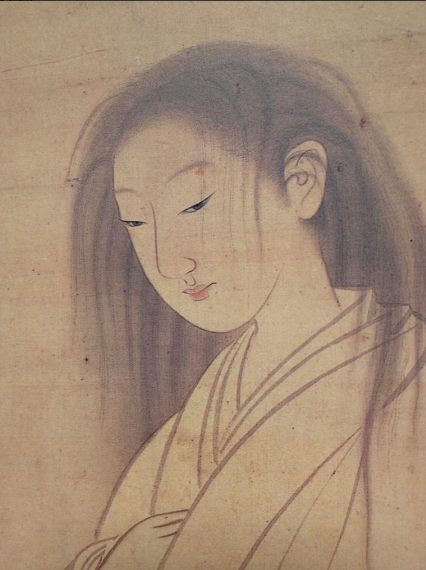

Maruyama Okyo, an ukiyo-e master of the Edo period, depicts for the fist time the spectre of Oyuki, a maid killed and thrown in a well for a missing dish. The artist renders her with those features which will constitute the traditional iconography of yuurei.

Maruyama Okyo, an ukiyo-e master of the Edo period, depicts for the fist time the spectre of Oyuki, a maid killed and thrown in a well for a missing dish. The artist renders her with those features which will constitute the traditional iconography of yuurei.  The white kimono katabira is typical of the funeral rituals, and also the hairdressing. Adult women in the Japanese tradition wore their hair in a bun, leaving them loose only the day of their funeral. The white dress and the mask of hair have been re-proposed to create the horror icon Sadako of the Ring cycle, composed by a novel (Koji Suzuki, 1991), a movie (Hideo Nakata, 1998) and a remake (Gore Verbinski, 2001).

The white kimono katabira is typical of the funeral rituals, and also the hairdressing. Adult women in the Japanese tradition wore their hair in a bun, leaving them loose only the day of their funeral. The white dress and the mask of hair have been re-proposed to create the horror icon Sadako of the Ring cycle, composed by a novel (Koji Suzuki, 1991), a movie (Hideo Nakata, 1998) and a remake (Gore Verbinski, 2001).

The West has the cultural habit of division, its underworld is closed by impassable limina, guarded by ferocious keepers: only exceptional heroes can cross the thresholds, and nothing can go out of them, in any case. In Japan instead, Meido (the world of dead) and Shaba (the world of living) are two parallel dimensions which subsist on the same plane of existence. Their relationship is more fluid, permeable, and their boundaries are less categorical. The in-betweens of these two worlds are not reported, and it’s possible to cross one of them by chance. That’s what happens to Chihiro, the protagonist of Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001), who all of a sudden gets landed with working in a beauty-farm of ghosts.

The West has the cultural habit of division, its underworld is closed by impassable limina, guarded by ferocious keepers: only exceptional heroes can cross the thresholds, and nothing can go out of them, in any case. In Japan instead, Meido (the world of dead) and Shaba (the world of living) are two parallel dimensions which subsist on the same plane of existence. Their relationship is more fluid, permeable, and their boundaries are less categorical. The in-betweens of these two worlds are not reported, and it’s possible to cross one of them by chance. That’s what happens to Chihiro, the protagonist of Spirited Away (Hayao Miyazaki, 2001), who all of a sudden gets landed with working in a beauty-farm of ghosts.

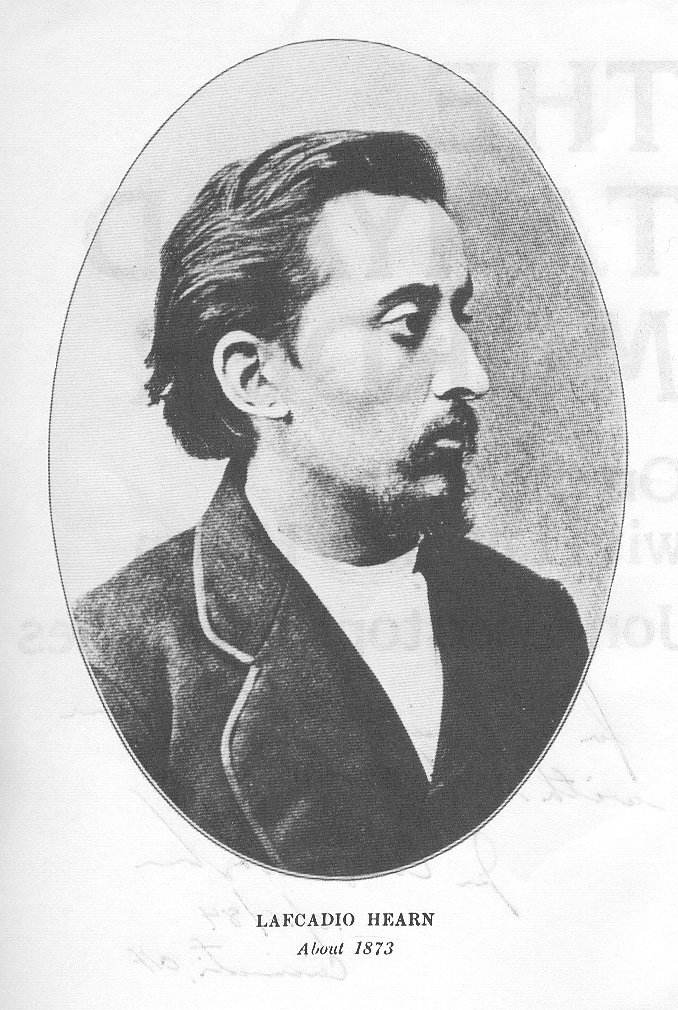

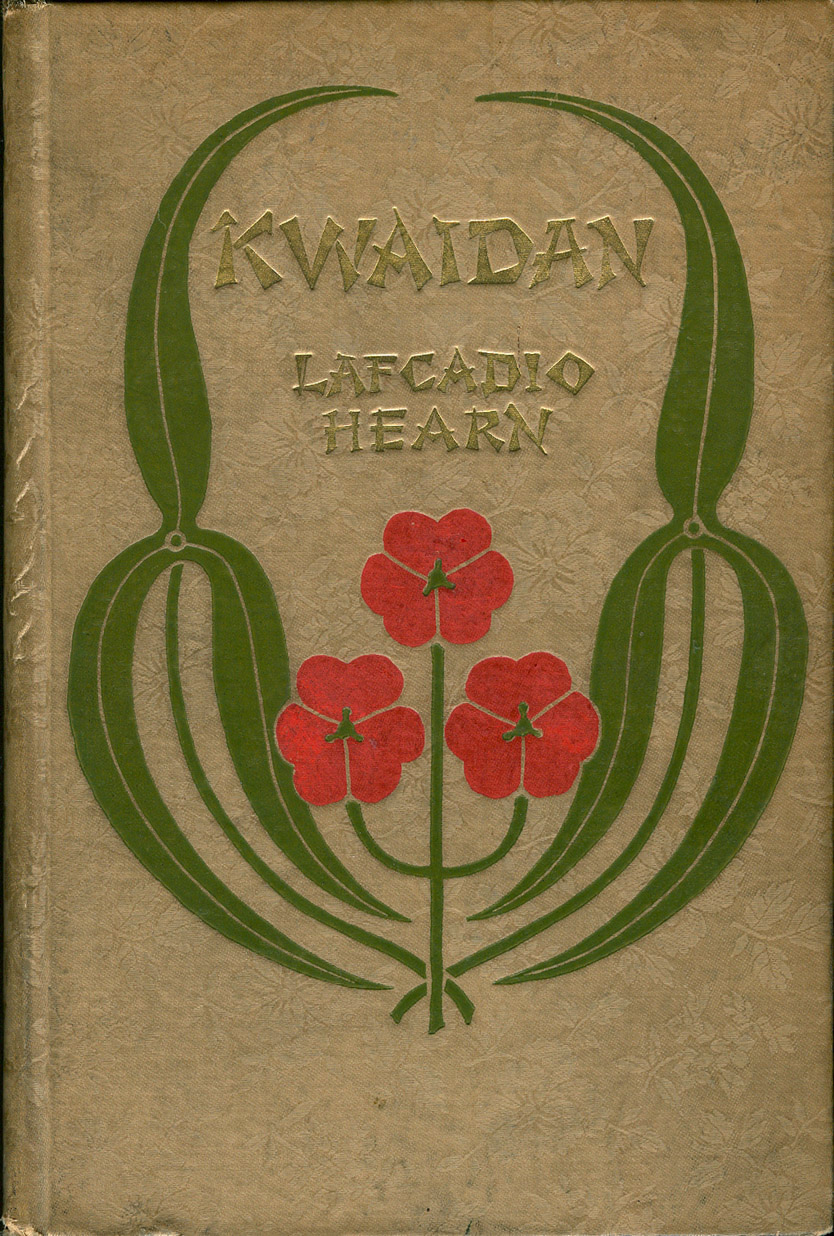

The fist Westerner who traced a topography of the Japanese netherworld was Lafcadio Hearn. Journalist in the America of the Nineteenth Century, he writes reports on the outsiders and on the voodoo rituals of New Orleans, getting illegally married with black women. He finally lands to Japan, where he marries the daughter of a distinguished family and becomes a samurai, with the name of Koizumi Yakumo.

The fist Westerner who traced a topography of the Japanese netherworld was Lafcadio Hearn. Journalist in the America of the Nineteenth Century, he writes reports on the outsiders and on the voodoo rituals of New Orleans, getting illegally married with black women. He finally lands to Japan, where he marries the daughter of a distinguished family and becomes a samurai, with the name of Koizumi Yakumo.  Lafcadio Hearn wrote many anthologies about spectres and local folklore, and he claimed that “Japan is a land ruled by the dead”.

Lafcadio Hearn wrote many anthologies about spectres and local folklore, and he claimed that “Japan is a land ruled by the dead”.  His Kwaidan was reworked by the filmmaker Masaki Kobayashi, for his homonymous movie. Kwaidan is the word for what is translated “horror” in the West.

His Kwaidan was reworked by the filmmaker Masaki Kobayashi, for his homonymous movie. Kwaidan is the word for what is translated “horror” in the West.

Remaining in the field of visual arts, Tom Na H-Iu is a real portal between the world of the dead and the world of the living, made by Mariko Mori, the queen of Japanese contemporaneous post-human style. In the Celtic mythology, Tom Na H-Iu is the limbo where the souls of dead people wait to reincarnate. This piece of art is a megalith made of glass, four and a half metres tall, illuminated by intelligent LED lights. A soft light throbbing in the dark. Plays, auroras, slow biological rhythms. These light sources are regulated by the connection with Super-Kamiokande, a neutrino observatory designed to search for proton decay and to catch the light of supernovas. Each time a star of the Milky Way dies, Mori’s work lights up. Supernovas are the biggest and the most powerful entities of the galaxy, and they go towards death too. The etymological root of desire (fundamental constituent of art, together with fear) is de-siderum, in which sidum-sideris means star. Life and death are the extreme terms of desire and fear.

Remaining in the field of visual arts, Tom Na H-Iu is a real portal between the world of the dead and the world of the living, made by Mariko Mori, the queen of Japanese contemporaneous post-human style. In the Celtic mythology, Tom Na H-Iu is the limbo where the souls of dead people wait to reincarnate. This piece of art is a megalith made of glass, four and a half metres tall, illuminated by intelligent LED lights. A soft light throbbing in the dark. Plays, auroras, slow biological rhythms. These light sources are regulated by the connection with Super-Kamiokande, a neutrino observatory designed to search for proton decay and to catch the light of supernovas. Each time a star of the Milky Way dies, Mori’s work lights up. Supernovas are the biggest and the most powerful entities of the galaxy, and they go towards death too. The etymological root of desire (fundamental constituent of art, together with fear) is de-siderum, in which sidum-sideris means star. Life and death are the extreme terms of desire and fear.

Miwa Yanagi represents the Windswept Women, defined as “old girls visiting from another world”. Screaming women, surrounded by whirls which stir up their hair, of an indefinable age. Some parts of their bodies are blooming, other ones wizened. There are plastic clouds around them, desolate mountain landscapes, fogs and moonshines. According to the Japanese culture of the past centuries, mountains have often been places of burial, considered holy. Mountains were the places of residence of another kind of beings: kami divinities, yukai with a grotesque appearance, the oni demons, riders of the clouds, the spirits of wind and thunder, and finally Yuma-Uba, female cannibal monsters, which constitute the folkloric transposition of a peculiar ancient habit, that is older women abandoned in the mountains by their poor families.

The Windswept Women seem a sort of synthesis of all these creatures, to demonstrate that in Japan the eighth hour has been repeating for millenniums, always, each night.

The Windswept Women seem a sort of synthesis of all these creatures, to demonstrate that in Japan the eighth hour has been repeating for millenniums, always, each night.

Published on Drome Magazine 19, The Supernatural Issue, spring 2011, p.88