A court of creepy little creatures, run away from the Goblin City in Labyrinth. Big eyes, bat-wings, little sharp teeth in a Muppet Show snout. A long before the Corpse Bride, blue China flesh, stitches, missing pieces: they are dolls with too much experience, long limbs, yellow eyes. Like cats, or like a Betty Boop with too many gin crates and opiates behind her. Liz McGrath uses the freaks’ pavilion like the ideal container for her imaginary.

A court of creepy little creatures, run away from the Goblin City in Labyrinth. Big eyes, bat-wings, little sharp teeth in a Muppet Show snout. A long before the Corpse Bride, blue China flesh, stitches, missing pieces: they are dolls with too much experience, long limbs, yellow eyes. Like cats, or like a Betty Boop with too many gin crates and opiates behind her. Liz McGrath uses the freaks’ pavilion like the ideal container for her imaginary.

Art has always speculated about its supports. Illuminated manuscripts, meta-theatre, trompe l’oeil, photographic pictures structured as Baroque paintings, meta-cinema, video and net art. Religious performances, cathartic rituals, windows on a space which doesn’t exist, the stage, the screens of motion-picture theatres, televisions and personal computers, till the 3D intrusions. One back-door station of this path was the freak-show indeed: people who paid to have the opportunity to look in the eyes their fellow creatures, disfigured by fate and nature. What should not exist, the dark side of their self. The freak lives a never-ending torment, such as the Christian martyrs frozen in pictures along the history of art. But live. To look upon sufferance is like peeping the mysteries of death. Before the TV-screen, freak-shows were atrocity exhibitions in presence, and therefore somehow more legitimate.

Scandal, fear, the comparison with our shadow have always been some of the basic ingredients of art. The Red-Cross nurse Frankie Machine left her legs at the front, from the knees to the feet, and she replaced them with a crinoline cage. Now Frankie has the right to claim that “Nemo liber est qui corpori servit”.

The Red-Cross nurse Frankie Machine left her legs at the front, from the knees to the feet, and she replaced them with a crinoline cage. Now Frankie has the right to claim that “Nemo liber est qui corpori servit”.

Also Miss Sugar Foot has the same mutilation, made by an axe. She has made for it grafting on a wheeled llama, with eyes as sweet as her missing feet.  Alpha Centauri has two small horns and a little sister, who didn’t want to part from her.

Alpha Centauri has two small horns and a little sister, who didn’t want to part from her.

Monsieur Poularde is a bird-boy, with mantle and cigar, friend of Ricky, the shark-boy.

Monsieur Poularde is a bird-boy, with mantle and cigar, friend of Ricky, the shark-boy.

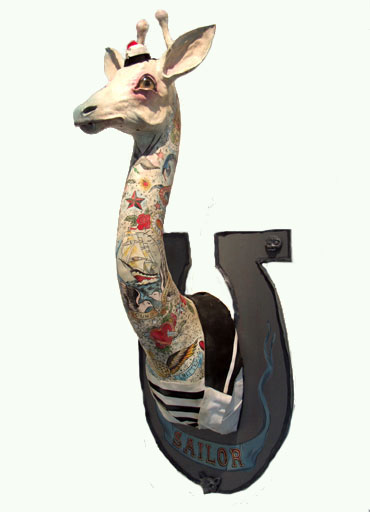

Liz McGrath has often represented freak-animals, squaring the otherness value of the subject. Before the machine, the animal was the opposite pole of the human, in which humans were mirrored and into which they poured the inadmissible features: luxury, violence, “bestiality”. We look at the reflection with more courage and honesty if they make us believe that it’s not ours. A pink fawn with three heads, one curious, one stolid, one distrustful. On its flank, a cameo with a majestic deer with antlered horns is dug, which is what the little monster would like to be, and would never become.

Animals which are emblems of human biographies: the sailor-giraffe, with its tattooed neck and a Gaultier shirt, once used to gaze into the distance, has ended pin down to somebody’s trophy.

Animals which are emblems of human biographies: the sailor-giraffe, with its tattooed neck and a Gaultier shirt, once used to gaze into the distance, has ended pin down to somebody’s trophy.

A bunny blue as the blues, with abandoned dog’s eyes, smudged with tears.  Sacrificial victims dressed to celebrate the gala day, pigs and horses divided in section.

Sacrificial victims dressed to celebrate the gala day, pigs and horses divided in section.  The trophy of a bear with amber-eyes, sacred-heart and two heads. One of them is howling and crying.

The trophy of a bear with amber-eyes, sacred-heart and two heads. One of them is howling and crying.

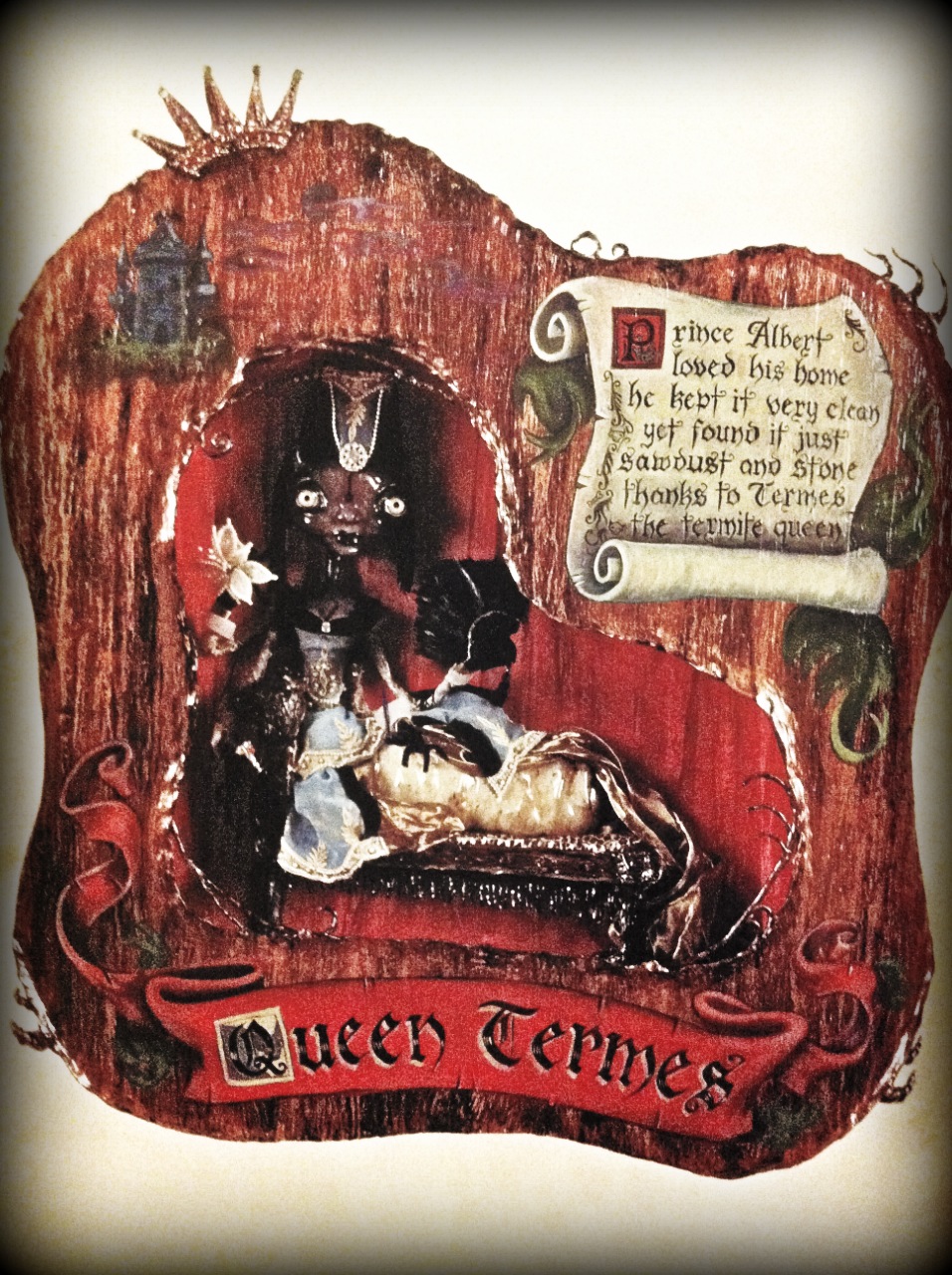

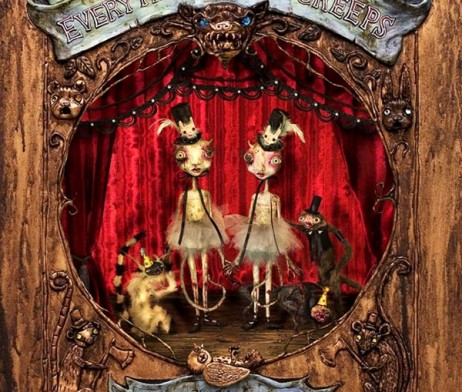

Liz McGrath digs into the layers of the history of vision, proposing jewel-boxes, something between the vaudeville theatre in the beginning of Twentieth Century, and religious aedicules.

She calls them Diorama, like the three-dimensional devices which were the borderline between painting and cinema. Inside of them, she places twins in ballet dress, with two-colour and wild eyes, accompanied by lemurs and flying rodents. On their little ghost bodies, the stigmata of the passion. Around them, an arabesque Gothic in Tim Burton style.

Around them, an arabesque Gothic in Tim Burton style.

A skeletal creature with branches coming out of her body and a black robe, holds in her arms the bones of a bird just come out of an egg, like a baby. In Honey Creeper McGrath mixes the iconography of the Virgin Mary with the one of the Great Mother, marrying them with the sepulchral aesthetics of the Nineteenth Century.

A skeletal creature with branches coming out of her body and a black robe, holds in her arms the bones of a bird just come out of an egg, like a baby. In Honey Creeper McGrath mixes the iconography of the Virgin Mary with the one of the Great Mother, marrying them with the sepulchral aesthetics of the Nineteenth Century.  This exploration of the recesses of the Christian iconology is also present in other works, like the white vampire corpse, carved with holes, closed in a cross-shaped coffin in Truth Decay.

This exploration of the recesses of the Christian iconology is also present in other works, like the white vampire corpse, carved with holes, closed in a cross-shaped coffin in Truth Decay. This attitude origins from Liz McGrath’s experience: a punk child in permanent clash with her parents, a former priest and a former nun, who locked her up at the age of thirteen in a boarding school of fundamentalist Baptists surrounded by a barbed wire fence. There she learned discipline and a lot of scary things about the Bible.

This attitude origins from Liz McGrath’s experience: a punk child in permanent clash with her parents, a former priest and a former nun, who locked her up at the age of thirteen in a boarding school of fundamentalist Baptists surrounded by a barbed wire fence. There she learned discipline and a lot of scary things about the Bible.

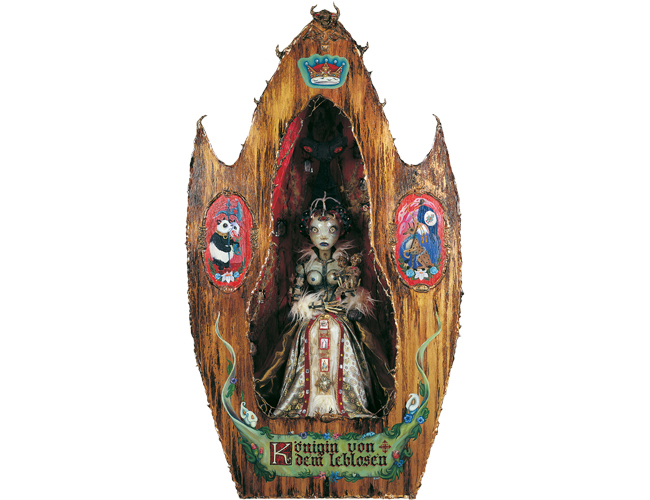

The Queen of the Inanimate has blue lips, and a scorpion holding a ruby between her eyes.  In her hand a little deformed foetus, with two heads, reading a book marked with number seven.

In her hand a little deformed foetus, with two heads, reading a book marked with number seven.  Like the seventh seal to broke, to have the final revelation. To show us the sanctity of the monster. To make us understand that we are the monster.

Like the seventh seal to broke, to have the final revelation. To show us the sanctity of the monster. To make us understand that we are the monster.

Published in November the 22th, 2010, on Lobodilattice