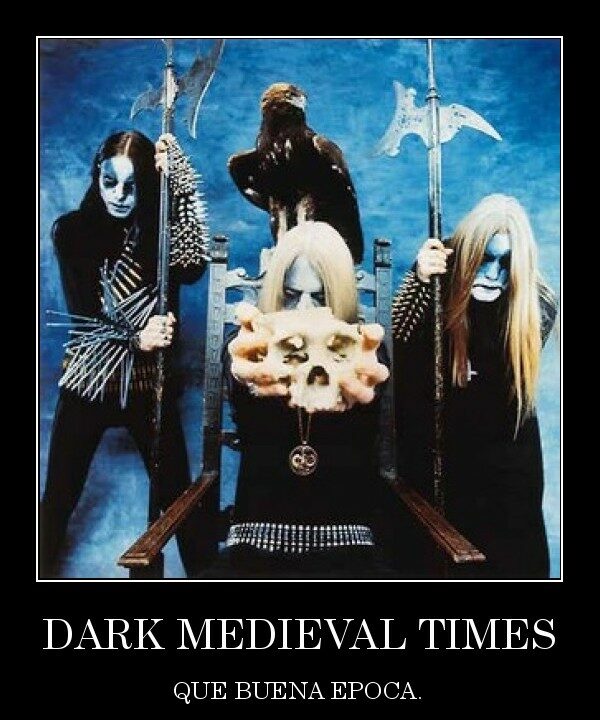

What historical period is more associated with darkness than the Middle Ages? One of our favorite songs from the black metal band Satyricon is aptly titled Dark Medieval Times, which is also the title of their first album. Dark Medieval Times is a heavy piece, with a powerful build-up. The part with the flute with its hippieish vibe is too funny, and we like the fact that after the flute the same tune is played by devastating guitars that feel like an axe.

What historical period is more associated with darkness than the Middle Ages? One of our favorite songs from the black metal band Satyricon is aptly titled Dark Medieval Times, which is also the title of their first album. Dark Medieval Times is a heavy piece, with a powerful build-up. The part with the flute with its hippieish vibe is too funny, and we like the fact that after the flute the same tune is played by devastating guitars that feel like an axe.

In this article, we will continue our historical examination of our favorite color, delving into the dark centuries. The association of the color black with the Middle Ages is not historically immediate. It starts with the symbolic connection of the color black to the laboratores class, the peasants, the poorest ones linked to the black soil, and therefore considered bad and inferior compared to everything noble and spiritually elevated, ideologically attributed to their rulers. In addition to the medieval negativity associated with the color black, there are also religious reasons related to biblical content, which becomes increasingly foundational to the mindset. Satan will become the darkest part of pictorial compositions, abandoning his traditional polychromy. A strange religious hatred also develops towards animals, especially black ones, upon which all the worst and unconfessed human characteristics are projected. During the Middle Ages, there is also the opposition between white monks and black monks, which marks the beginning of the opposition between black and white. The color black is reevaluated in the Carolingian era as a symbol of modesty and, with the beginning of heraldry, as a noble color, and will finally resurge as the color of a new revolutionary medium that will wipe the Dark Ages away. Let’s now analyze all these events in detail.

In this article, we will continue our historical examination of our favorite color, delving into the dark centuries. The association of the color black with the Middle Ages is not historically immediate. It starts with the symbolic connection of the color black to the laboratores class, the peasants, the poorest ones linked to the black soil, and therefore considered bad and inferior compared to everything noble and spiritually elevated, ideologically attributed to their rulers. In addition to the medieval negativity associated with the color black, there are also religious reasons related to biblical content, which becomes increasingly foundational to the mindset. Satan will become the darkest part of pictorial compositions, abandoning his traditional polychromy. A strange religious hatred also develops towards animals, especially black ones, upon which all the worst and unconfessed human characteristics are projected. During the Middle Ages, there is also the opposition between white monks and black monks, which marks the beginning of the opposition between black and white. The color black is reevaluated in the Carolingian era as a symbol of modesty and, with the beginning of heraldry, as a noble color, and will finally resurge as the color of a new revolutionary medium that will wipe the Dark Ages away. Let’s now analyze all these events in detail.

MEDIEVAL BLACK IN SOCIETY ROLES AND RELIGION

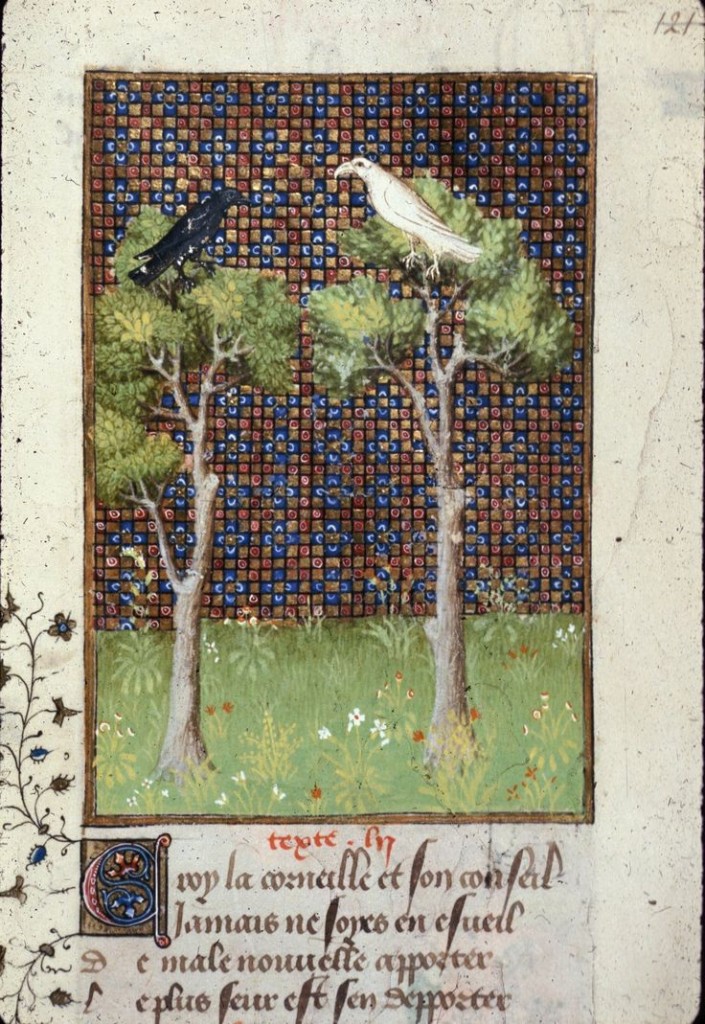

In the Middle Ages, there was a strong association of colors with different societal roles. White was associated with priests, red with warriors, and black with peasants, who were responsible for food supply due to their close connection with the earth. In Christian civilization, black was often connotated negatively (though not always). During the early Middle Ages, the concept of both “good black” and “bad black” from Roman times persisted. The term “Sheol” in the Bible referred to the hell for sinners, a place of pain, gnashing of teeth, and darkness. The black raven was considered a messenger of misfortune and death after the flood. In the New Testament, an epithet of the devil is “Prince of Darkness.”

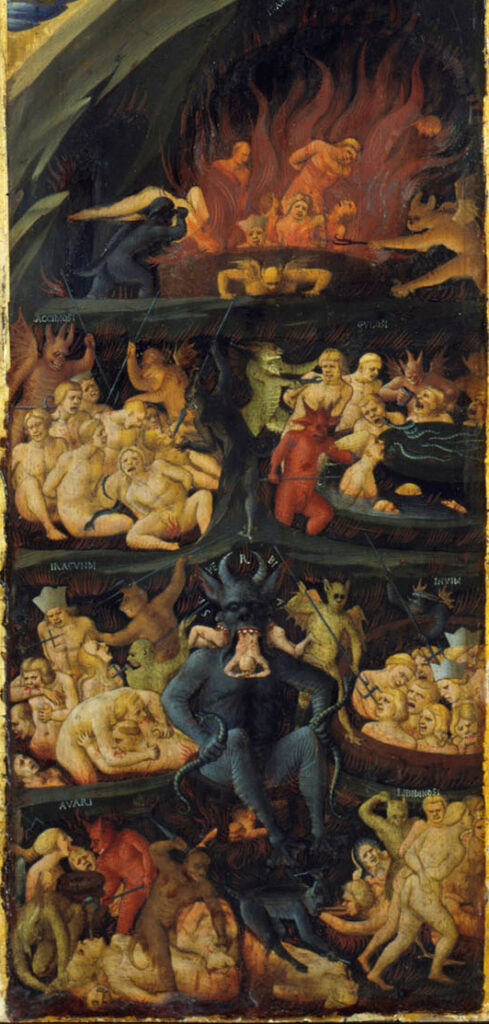

However, towards the end of the Carolingian era, black was reevaluated as a symbol of penance and modesty, especially after it was adopted as the color of the Benedictine friars’ habit. Christian festivities had specific colors: white was associated with the Virgin Mary, angels, and Christ; red symbolized the Holy Week of Passion; black was used for masses for the deceased, penitential periods like Lent, and times of waiting, like Advent. With the rise of feudalism, particularly from the 11th century onward, black’s negative connotation strengthened. Darkness became part of the infernal punishments, and black finally became the color associated with the devil, which was previously polychrome. Purple and blue were also assimilated to black, leading blue to have a bad reputation for a long time before being rehabilitated as the color of the Virgin Mary’s mantle.

SATAN’S FAVORITE BLACK PETS

In the figurative arts, the black of devils, particularly Satan, is always the most intense in the entire composition, whether it’s a fresco or a miniature, and it seems to absorb all the surrounding light.

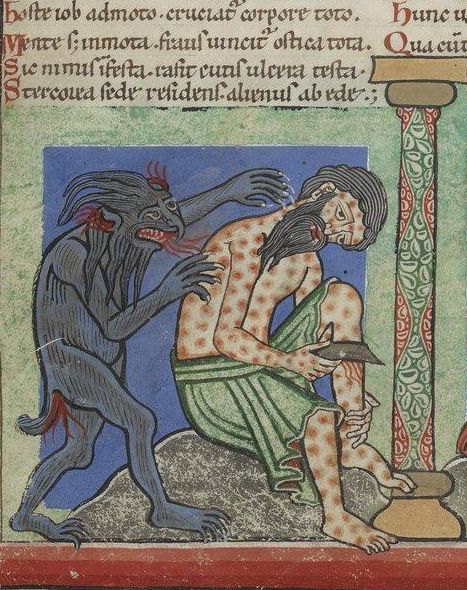

Then there are all the animals from the bestiary of the Prince of Darkness. One of the most peculiar characteristics of medieval mentality is symbolism, where everything that appears in creation is a message from God, to be deciphered by knowing the code of symbols.

Then there are all the animals from the bestiary of the Prince of Darkness. One of the most peculiar characteristics of medieval mentality is symbolism, where everything that appears in creation is a message from God, to be deciphered by knowing the code of symbols.

The scavenging crow is considered a malevolent creature; the Church Fathers deem it very vicious, perhaps recalling all the effort their colleagues had to put into eradicating its worship.

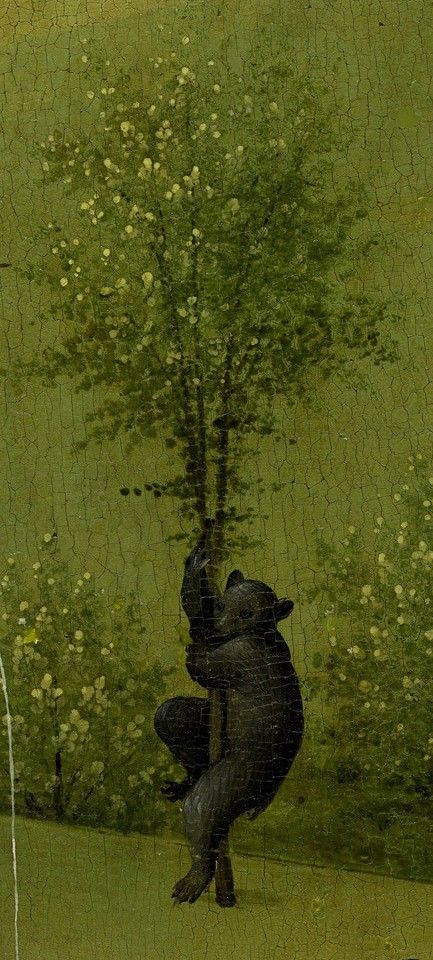

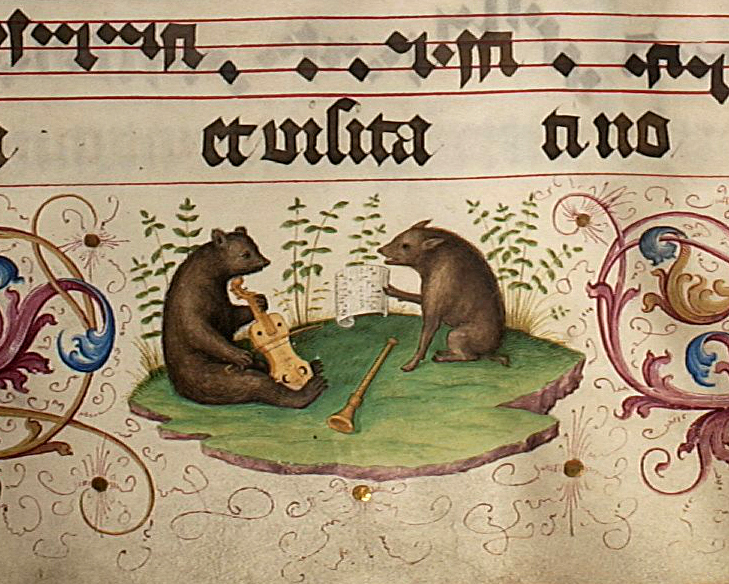

The bear is deemed similar to humans, just as the monkey is in the regions of Africa and India. Among the Celts, Germans, and Slavs, there are many warrior cults dedicated to the bear. Its flesh and blood are consecrated food to be consumed before battles, to appropriate its strength and courage. Royal lineages boast of bear origins, with ancestresses abducted by bears and united with them. Therefore, the Church demonizes it, and Saint Augustine affirms that “the bear is the devil.” It is dark-furred, and every winter it descends into hell to hibernate in warmth.

The bear is deemed similar to humans, just as the monkey is in the regions of Africa and India. Among the Celts, Germans, and Slavs, there are many warrior cults dedicated to the bear. Its flesh and blood are consecrated food to be consumed before battles, to appropriate its strength and courage. Royal lineages boast of bear origins, with ancestresses abducted by bears and united with them. Therefore, the Church demonizes it, and Saint Augustine affirms that “the bear is the devil.” It is dark-furred, and every winter it descends into hell to hibernate in warmth.

The cat, due to its nocturnal habits, sinuous beauty, and phosphorescent eyes, is regarded with suspicion. Despite its utility as a hunter, for a long time, the ferret is preferred for rat-catching. In the late 15th century, Pope Innocent VII excommunicates all cats. Two centuries earlier, Gregory IX had officially proclaimed that black cats are forms assumed by the Malevolent in the world and should therefore be exterminated through burning, crucifixion, or flaying. On the night of St. John, thousands of cats are burned alive in cages placed in the main squares of cities or thrown from bell towers.

The cat, due to its nocturnal habits, sinuous beauty, and phosphorescent eyes, is regarded with suspicion. Despite its utility as a hunter, for a long time, the ferret is preferred for rat-catching. In the late 15th century, Pope Innocent VII excommunicates all cats. Two centuries earlier, Gregory IX had officially proclaimed that black cats are forms assumed by the Malevolent in the world and should therefore be exterminated through burning, crucifixion, or flaying. On the night of St. John, thousands of cats are burned alive in cages placed in the main squares of cities or thrown from bell towers.

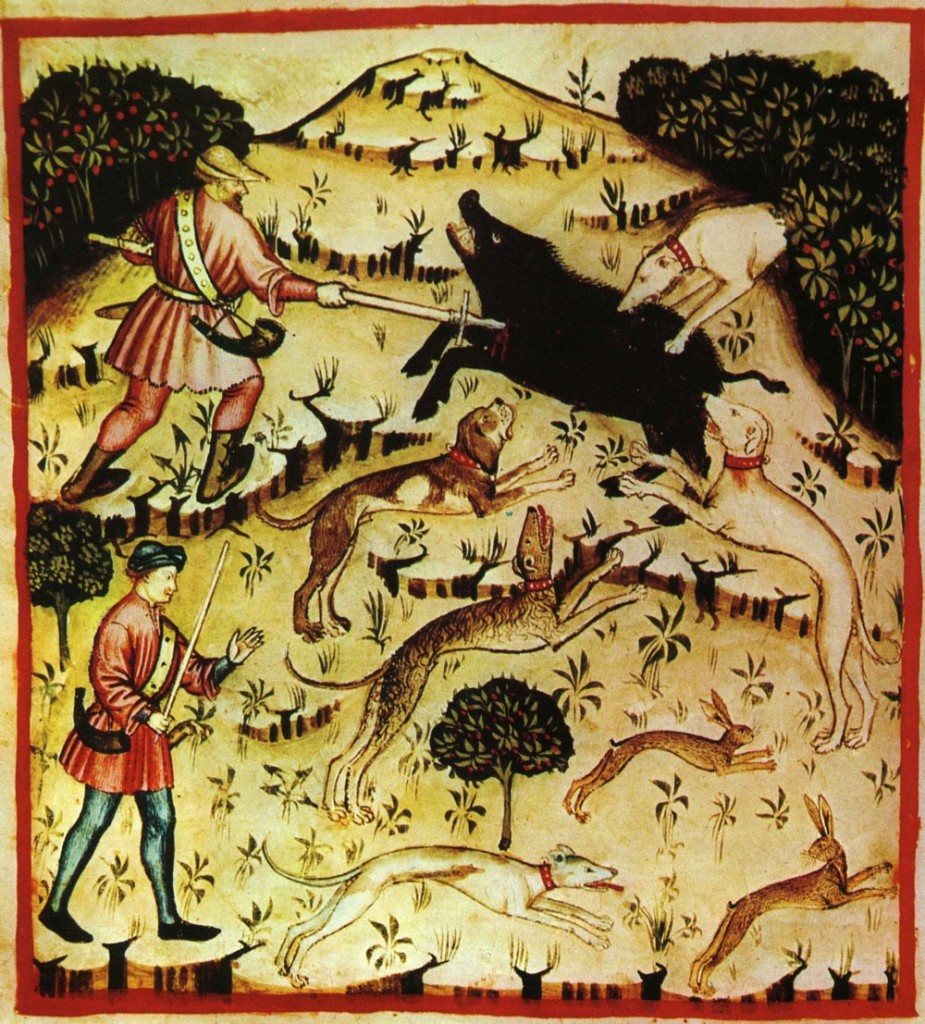

The wild boar, to whom the cults of the Great Mother were once dedicated, is supremely demonized. Preachers consider it a true incarnation of Satan due to its black hide, tusks, and stench.

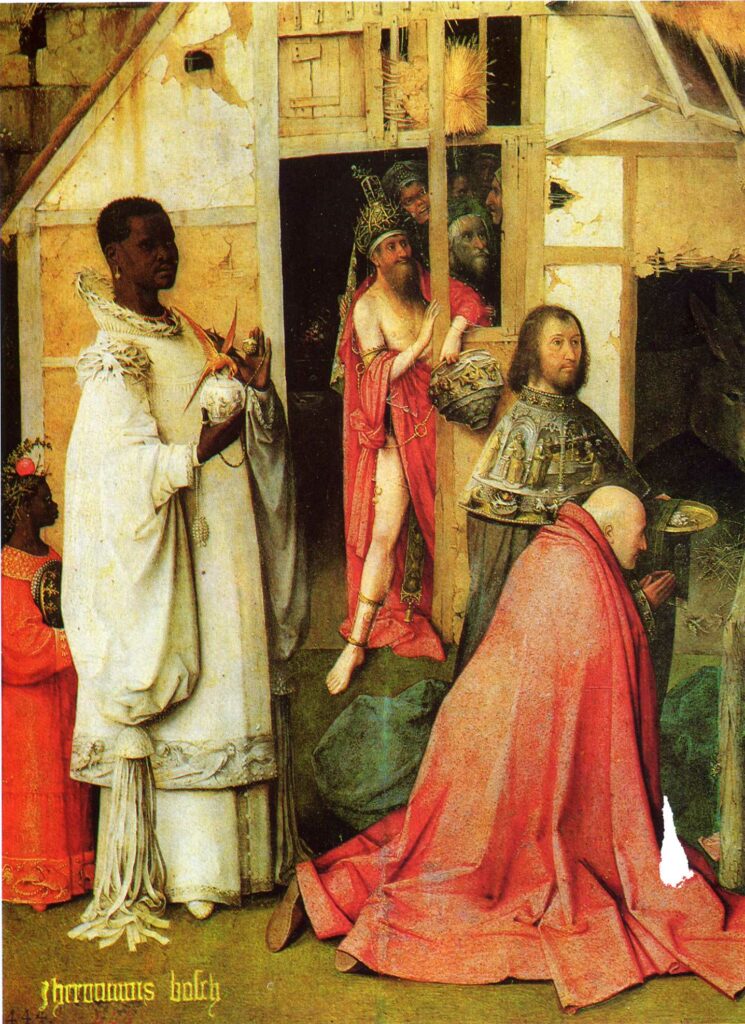

MORALIZING THE RACE

In medieval art and literature, negative characters were often depicted with dark skin. For instance, Judas, the betrayer of Christ, was portrayed with red hair and dark skin. In epic poems, the Saracens were often described as having darker skin, and the darker the skin tone of a character, the more wicked they were believed to be. Around the 14th century, new characters appeared in the collective imagination, such as the Queen of Sheba, depicted as “black but beautiful” like the protagonist in the Song of Songs. Dark skin began to be seen as exotic, indicating a feeling of intriguing diversity.  During the 14th century, the biblical Magi, particularly King Balthasar representing Africa, began to be depicted with black skin. The mixing of cultures led to conversions from Islam to Christianity, and the other way around.

During the 14th century, the biblical Magi, particularly King Balthasar representing Africa, began to be depicted with black skin. The mixing of cultures led to conversions from Islam to Christianity, and the other way around.

BLACK AND WHITE MONKS (AND ALSO GREY)

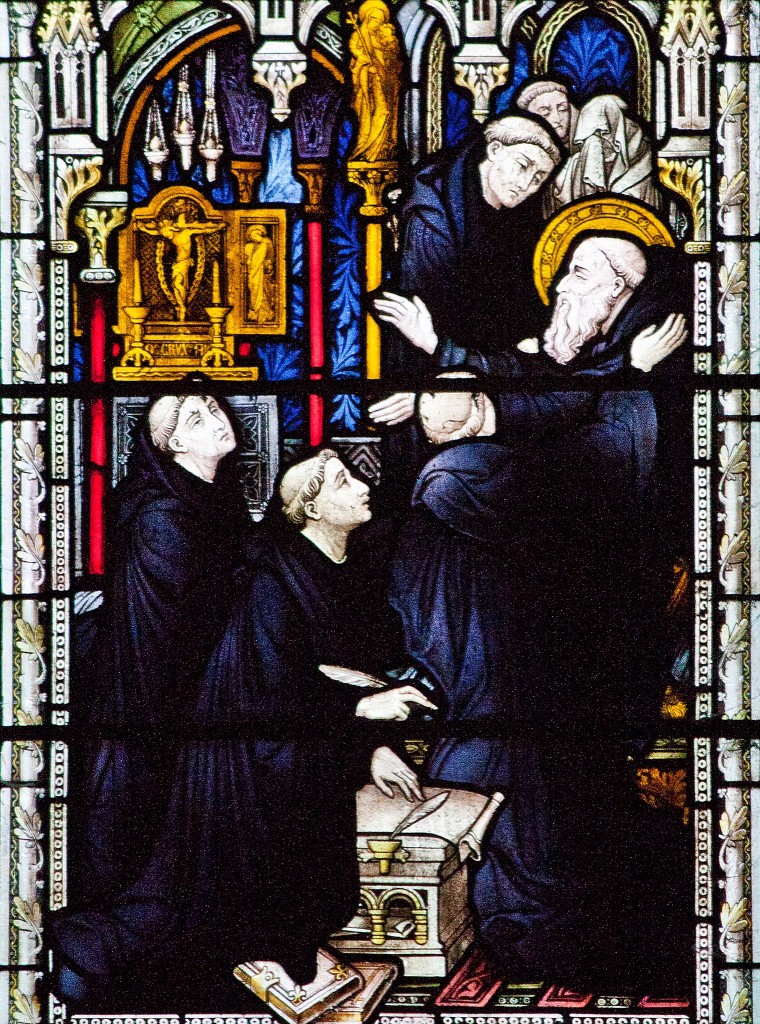

In the early 12th century, there was a chromatic dispute between the white and black monks. Saint Benedict, the founder of monasticism in the 6th century, believed that monks’ attire should resemble that of peasants, reflecting humility, and should not be dyed. However, by the Carolingian era, the Benedictine habit was already a type of uniform, if not black, at least of dark colors. Until the 14th century, obtaining truly black textiles was challenging. The Benedictines adopted black as a symbol of penance, leading people to call them “monachi nigri” (black monks).

In the 12th century, the Cistercian order emerged, which initially dressed in gray like dissidents to return to the austerity of their origins. Later, they shifted to white, as they were hostile to colors, ostentation, and decorations, preferring a monochromatic and unadorned church environment.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the founder of the order, detests gold and goldsmithing, stained glass, and polychrome miniatures, and is chromophobic. Therefore, he decides to have his followers dressed in white. In reality, until the 18th century, obtaining pure white textiles was impossible because the bleaching process using chlorine was not known. People had to settle for naturally bleached colors, which tended to become shades like cream, ecru, or gray through lengthy and difficult methods, such as using the oxygenated water from morning dew.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the founder of the order, detests gold and goldsmithing, stained glass, and polychrome miniatures, and is chromophobic. Therefore, he decides to have his followers dressed in white. In reality, until the 18th century, obtaining pure white textiles was impossible because the bleaching process using chlorine was not known. People had to settle for naturally bleached colors, which tended to become shades like cream, ecru, or gray through lengthy and difficult methods, such as using the oxygenated water from morning dew.

Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny and lover of extreme luxury, adorned in his black robe lined with sable, argues that the choice of the Cistercians is indecent and goes against tradition. He vehemently accuses St. Bernard of Clairvaux of pride because, until then, white had been reserved only for solemn liturgies, while the Cluniacs humbly dressed in black following the Benedictine rule. St. Bernard of Clairvaux counters that black is the color of death and sin, whereas white is a symbol of purity.

Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny and lover of extreme luxury, adorned in his black robe lined with sable, argues that the choice of the Cistercians is indecent and goes against tradition. He vehemently accuses St. Bernard of Clairvaux of pride because, until then, white had been reserved only for solemn liturgies, while the Cluniacs humbly dressed in black following the Benedictine rule. St. Bernard of Clairvaux counters that black is the color of death and sin, whereas white is a symbol of purity.

The 12th century marked the beginning of opposition between white and black, which were not considered opposites until then. Red and white were considered opposites instead.

NOBLE BLACK REVALUATION

The development of heraldry around the mid-12th century further paved the way for the revaluation of black. Heraldry used distinctive signs in military attire, required by new helmets and armor that concealed the knights’ features. The colors used in heraldry were limited to six: white (argent), black (sable), yellow (or), red (gueules), blue (azur), and green (sinople). The word that indicates black, “sable,” comes from Slavic languages and refers to the sable fur, which was highly coveted and traded as a luxury item in the Middle Ages. It was commonly used by Russian nobles and the Polish szlachta.

With heraldry’s introduction, black began to be ennobled and dissociated from demonic connotations. In literary works, mysterious black knights started to appear in chivalric romances, not necessarily as negative characters, but often as the heroes themselves, concealing their identities to advance the narrative. This shift can be seen, for example, when Walter Scott dressed Richard the Lionheart in black upon his return from the Holy Land in “Ivanhoe.” Usually, the evil knight is the one in red, as is also the case in contemporary cinema with “The Fisher King,” a medieval redemption fable set in Manhattan.

With heraldry’s introduction, black began to be ennobled and dissociated from demonic connotations. In literary works, mysterious black knights started to appear in chivalric romances, not necessarily as negative characters, but often as the heroes themselves, concealing their identities to advance the narrative. This shift can be seen, for example, when Walter Scott dressed Richard the Lionheart in black upon his return from the Holy Land in “Ivanhoe.” Usually, the evil knight is the one in red, as is also the case in contemporary cinema with “The Fisher King,” a medieval redemption fable set in Manhattan.

THE BEGINNING OF MODERN BLACK

INK AND MOVABLE TYPE PRINTING

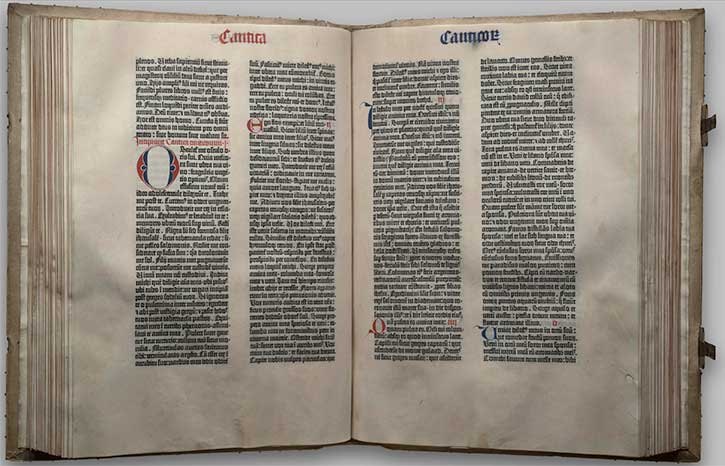

The transformation of white into something equivalent yet opposite to black has occurred gradually. As a preliminary step, there was a chromatic dispute between Cistercians and Cluniacs, but the true inception was marked by the invention of movable type printing. A resistant, glossy, deep black ink began to be employed, significantly distinct from the ink manually scribed by amanuensis, which could be scraped away. Printing ink penetrated deeply into the fibers of paper and resisted fading due to the weight of the presses, inspired by those used by Rhineland vintners. This durability was also aided by chemical reactions resulting from the introduction of new substances. Each printing house guarded its own secret recipe, yet they all bore a resemblance to the formula crafted by Gutenberg during his time in Strasbourg in 1440. This formula was utilized fifteen years later for the creation of the 42-line Bible. Generally, this recipe entails a base akin to that of amanuensis—ivory or vine wood black, diluted in water or wine, and made viscous by binders like honey, Arabic gum casein, oil, or egg white. To this, linseed oil, iron or copper sulfate, and metallic salts are added, causing a chemical reaction between the paper and ink that renders it indelible, as evidenced by the forty-nine surviving copies of Gutenberg’s Bible, perfectly legible over five hundred and fifty years later.

The ubiquity of typographical black adheres everywhere, diffusing its characteristic scent. Typesetters become a disruptive and tumultuous category of workers, almost a subculture, always in haste, blackened from head to toe like charcoal burners, seen as dangerous by authorities due to being for the first time in modern history both physical toilers and literate laborers —a potent combination with a great potential to articulate the anger and disrupt establish norms. Their workshops must absolutely not reside in the upper quarters, for they resemble infernal forges.

Alongside ink, it’s paper that triggers the birth of a black-and-white world. Invented by the Chinese and brought to Europe by the Arabs, it appeared in Spain at the end of the 11th century and in Sicily at the beginning of the 12th century. It started being used for notarial acts in Italy, France, England, and Germany. The paper industry developed in parallel with the textile industry, which was oriented towards producing shirts, i.e., intimate garments worn by men and women, from the scraps of which paper material was made. Until the end of the 18th century, paper remained a costly item. With the invention of printing, the color of paper shifted from beige to ice white and ultimately true white. The union of black and pure white would lead to a genuine image revolution. While medieval images were polychromatic, modern ones tended toward black and white. In the mid-14th century, woodcut printing was invented and by 1460, it was integrated into book production. The black and white of woodcuts and engravings allowed for powerful effects of rhythm, shading, brilliance, density—all achieved through skillful use and calibrated juxtaposition of lines, which could be double, broken, intersecting, curved, thin, or thick.

_End Of the Second Part of TOTAL BLACK_

In the next chapter of this piece, we will investigate the Beginnings Of Black Fashion and Royal Black. The very next article will be about Kainowska and the History of the Wicked son of Adam, Cain, through Literature, Poetry, Music, and Religion... Stay tuned through our Facebook and Instagram!

Bibliography & Discography

If you enjoyed this article and are interested in delving deeper into the topic, you can find some bibliography in the following links. If you appreciate our content and would like to support the activities of our site, you can make purchases through these links, not necessarily limited to books listed in the bibliography but any kind of item. To do so, simply access the link and then fill your cart. Thanks to everyone!

Satyricon, Dark Medieval Times

Michel Pastoureau, Black: History of a Color.