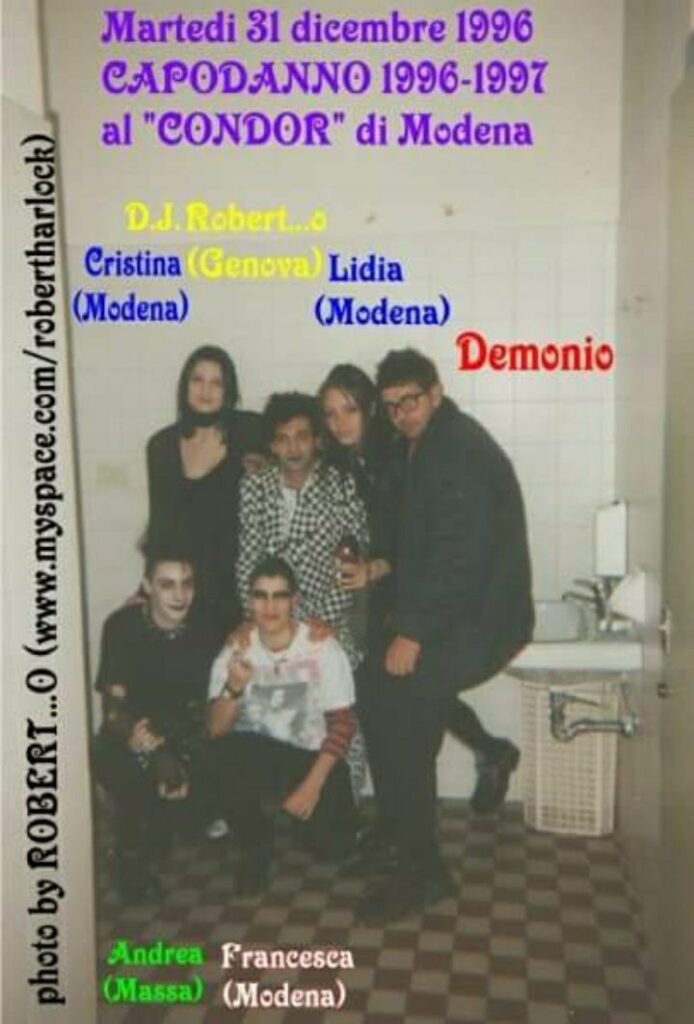

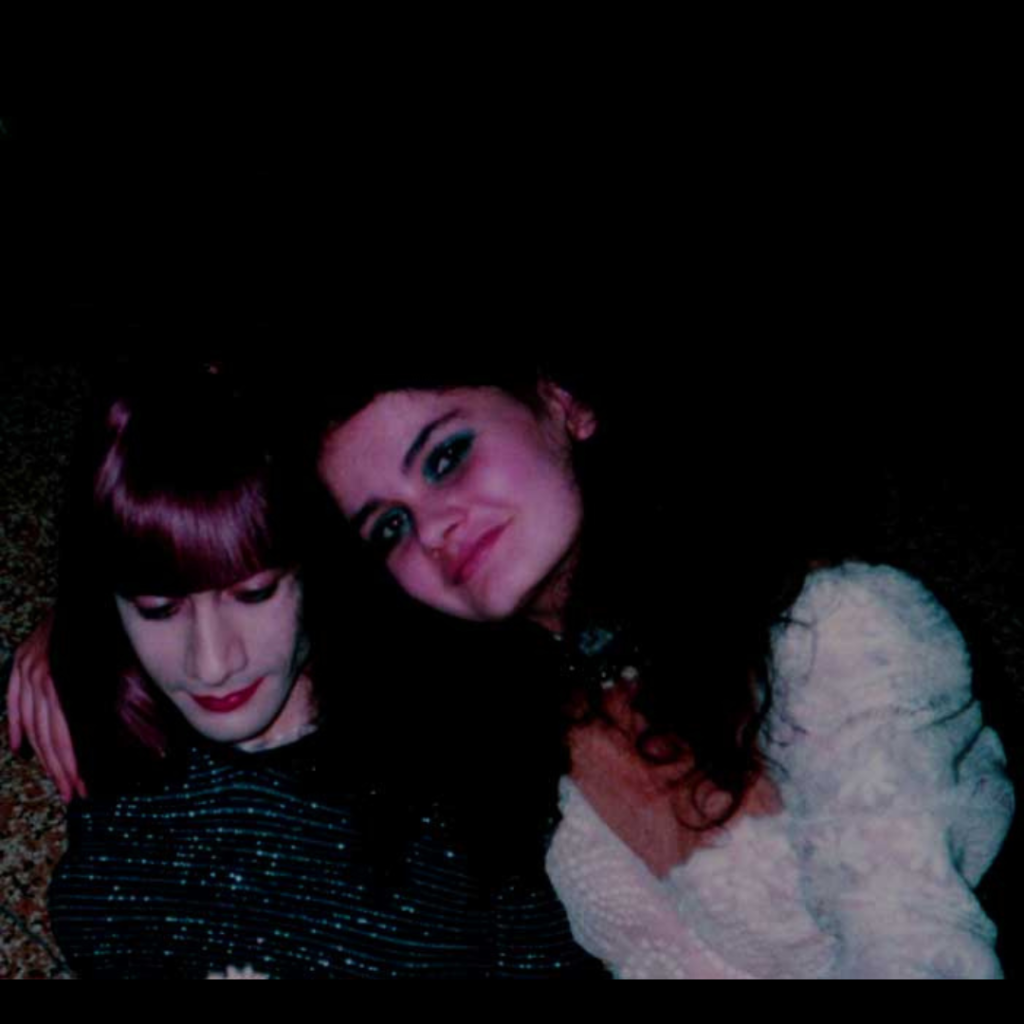

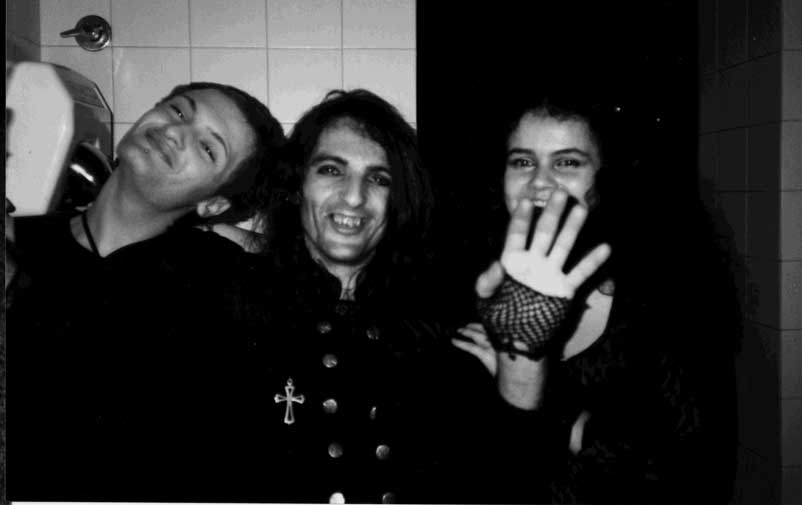

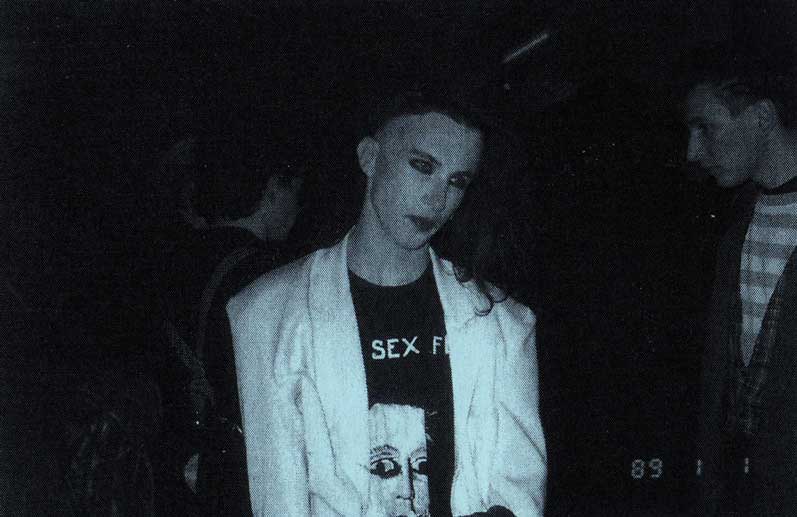

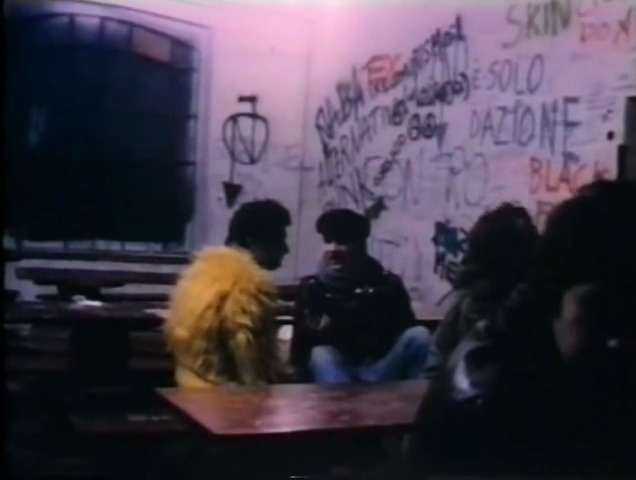

During our rather solitary, quirky, nomadic, and unaffiliated early youth, there was a place that, throughout our psychogeographical explorations of subcultures, we frequented and perhaps loved more than any other. We loved it for various reasons. First of all, the music was dope. Death in June, Athamay, Public Image Limited, Virgin Prunes. Everything seemed frozen in time, like an abandoned film set, and everything had come to a standstill in the 1980s: cold neons, darkness, mirrors, couches everywhere, rotating lights. There were unisex restrooms; sometimes you’d go to the women’s, other times to the men’s, and in both, you’d have great conversations and take lots of disposable camera photos.

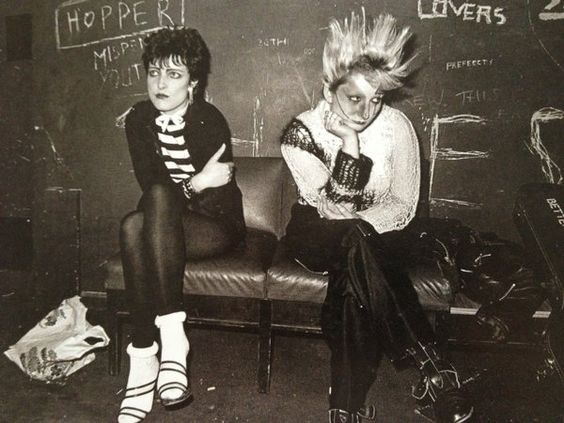

During our rather solitary, quirky, nomadic, and unaffiliated early youth, there was a place that, throughout our psychogeographical explorations of subcultures, we frequented and perhaps loved more than any other. We loved it for various reasons. First of all, the music was dope. Death in June, Athamay, Public Image Limited, Virgin Prunes. Everything seemed frozen in time, like an abandoned film set, and everything had come to a standstill in the 1980s: cold neons, darkness, mirrors, couches everywhere, rotating lights. There were unisex restrooms; sometimes you’d go to the women’s, other times to the men’s, and in both, you’d have great conversations and take lots of disposable camera photos.  Everyone who went there was a freak. You could run into the supreme kings of power electronics music, slightly geeky Stephen King clones with bottle-bottom glasses and visible tracheotomies, malevolent dark elves talking about Violence and Lies, dominatrixes with Diamanda Galas faces and 6.7-inch heels accompanied by nerds in jumpsuits, and a punk girl standing at 6’2″ with Claudia Schiffer face and an Earth A.D. shirt, who had the remarkable ability to bring the entire venue to a standstill as she danced to CCCP’s “Curami” on the dance floor.

Everyone who went there was a freak. You could run into the supreme kings of power electronics music, slightly geeky Stephen King clones with bottle-bottom glasses and visible tracheotomies, malevolent dark elves talking about Violence and Lies, dominatrixes with Diamanda Galas faces and 6.7-inch heels accompanied by nerds in jumpsuits, and a punk girl standing at 6’2″ with Claudia Schiffer face and an Earth A.D. shirt, who had the remarkable ability to bring the entire venue to a standstill as she danced to CCCP’s “Curami” on the dance floor.

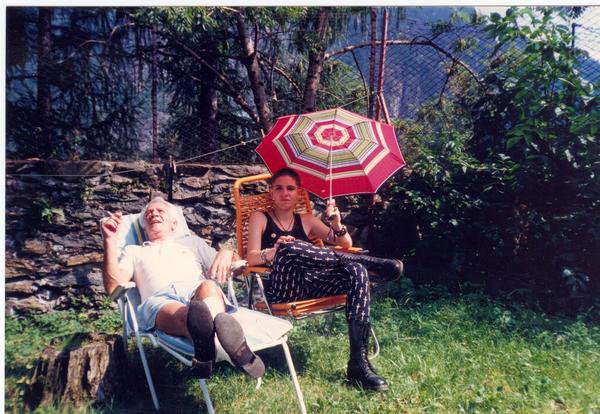

All subcultures passed through, from punks to metalheads, from goths to skinheads. There were sleazy solicitors from the train station, fashionable addicts camouflaged in glitter, kinderwhores with their daddies, and trans folks bitchy, vicious, and ugly as sin. Image was important, but it was fine even if you were worn out, tasteless, not so good-looking, unkept, anorexic, fat, sad. There was no need for any crappy door selection, because decay was real and radical, it came from within and had finally found a place to flourish. To enter, you climbed a staircase that spiraled with an incredibly theatrical elliptical rotation, and the air inside was filled with great energy. There was a contradictory atmosphere, blending between a grand celebration and the aftermath of a party, carrying a sense of Fellinian melancholy akin to the carnival in “I Vitelloni.” This place was very hospitable; you’d go there, and after a while, despite your autism issues, you knew everyone.

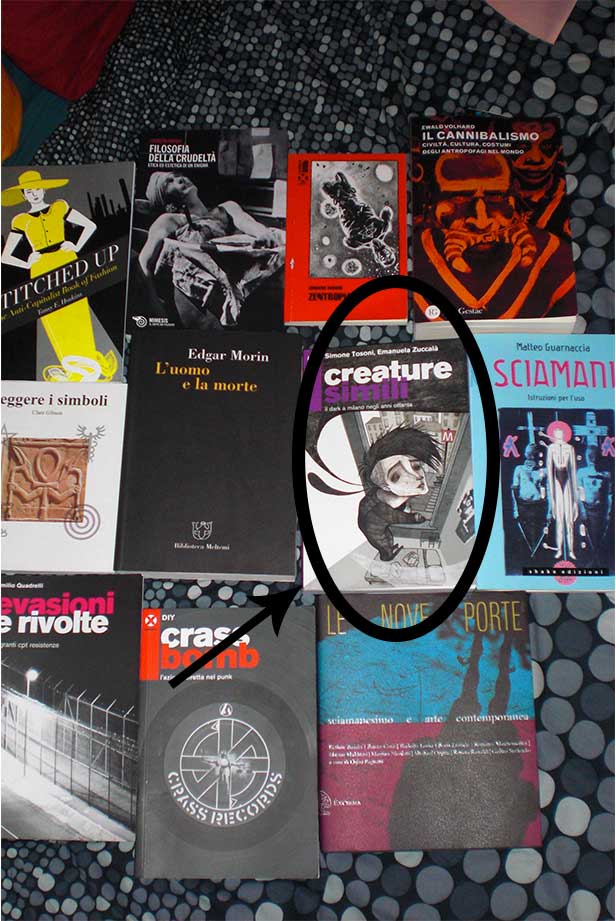

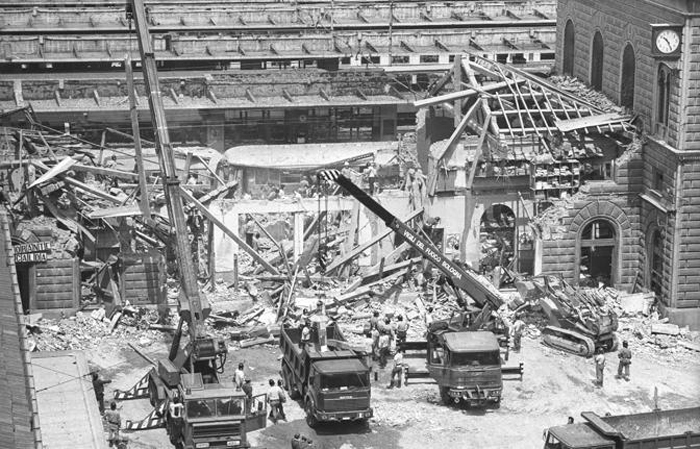

Fulfilling its destiny as an “einstürzende neubauten,” this nightclub has now been demolished, and we haven’t even seen its ruins. But some years ago, at the Turin Book Fair, we stumbled upon a marvelous essay that historicizes that social, aesthetic, and cultural wave that also led to the existence of the Condor, which we loved so much.

The essay “Italian Goth Subculture. Kindred Creatures and Other Dark Enactments 1982-1991” explores the birth and development of the dark/goth movement in Italy, with the epicenter being 1980s Milan. In this article, we will provide a transversal overview of Simone Tosoni and Emanuela Zuccalà‘s treatise, considering both the historiography and geography of the movement, as well as two elements that have always interested us specifically: clothing aesthetics, especially those leaning toward black, and self-produced publications. Tosoni and Zuccalà have structured the essay giving utmost importance to the words of the protagonists. Since nothing can be more revealing than the statements of those who lived a certain moment and a particular reality, this analysis of the Italian goth subculture will also include quotes from those who were part of the dark scene in Milan and its surroundings in the early 1980s.

NOMENCLATURES

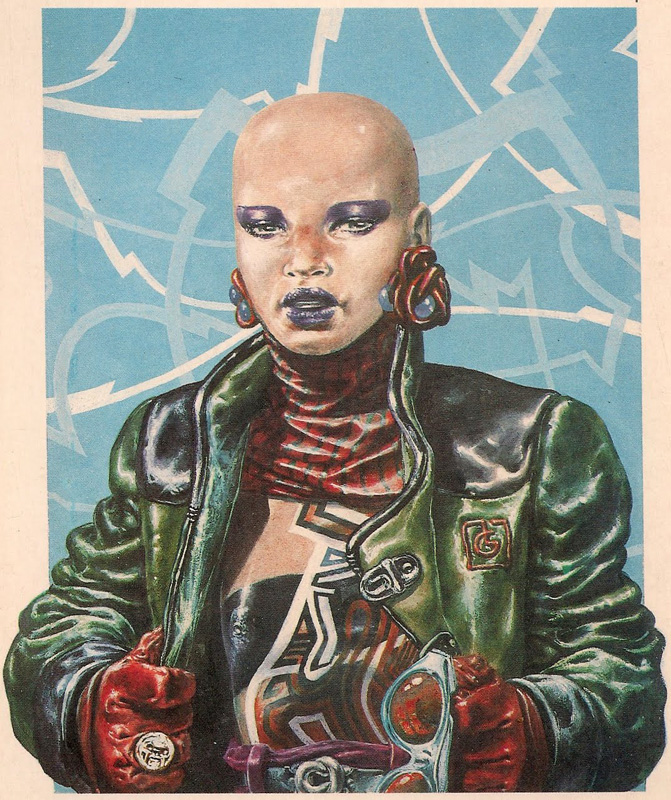

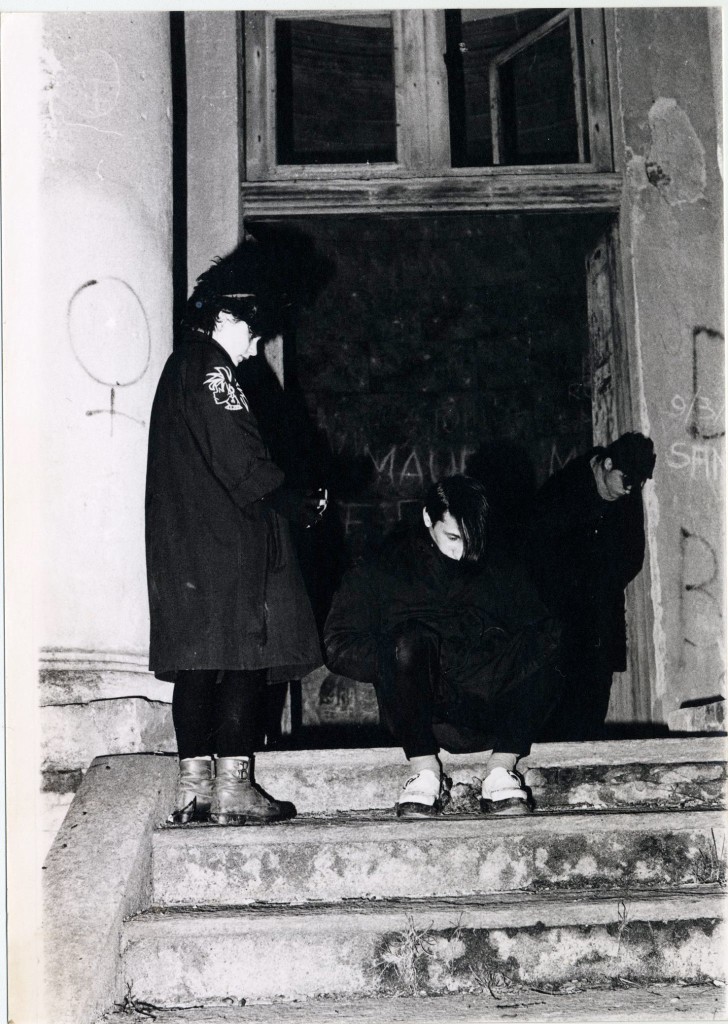

“Dark” is a term that only exists in Italy. This subculture, which conventionally originated in England at the Batcave nightclub, is now universally referred to as “goth,” with all the fashionable variations of recent years: cyber goth, gothic Lolita, gothic aristocrat, fetish goth, tribal goth, goth metal, emo, neo-folk. The term “goth” was never exported to Italy, or at least it never took root outside the circle of the black-clad affiliates.

When the first pale punks began to appear in Milan, dressed head to toe in black and not involved with the street clashes so common in the city at that time, there wasn’t a definition for them. Some of them proudly referred to themselves as “gothic punks,” like the Batcave attendees. Later, in interactions with orthodox punks and squatting social centres, the term “Creature Simili” emerged, meaning Kindred Creatures. Eventually, the Italian media adopted the term “dark.” These are also the two primary elements of the early Italian gothic scene: anarchic Kindred Creatures on one side and the nightclub-goers on the other, with the Hysterika attendants leading the way. Another distinct universe was the provincial dark scene, operating in socially more hostile territories than Milan.

THE 1980s IN MILAN

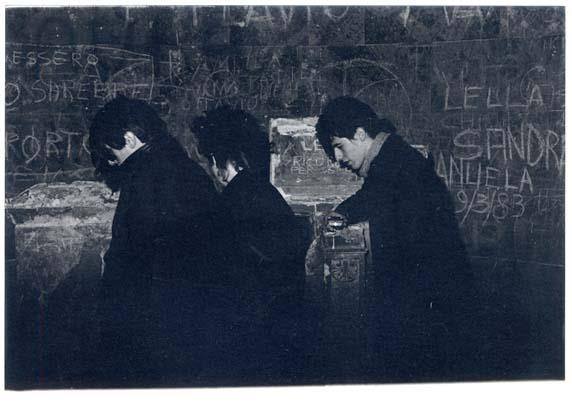

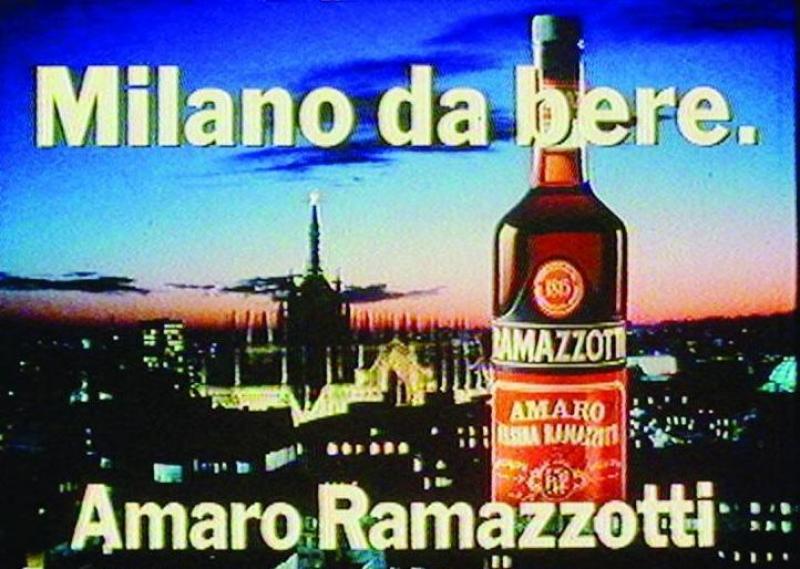

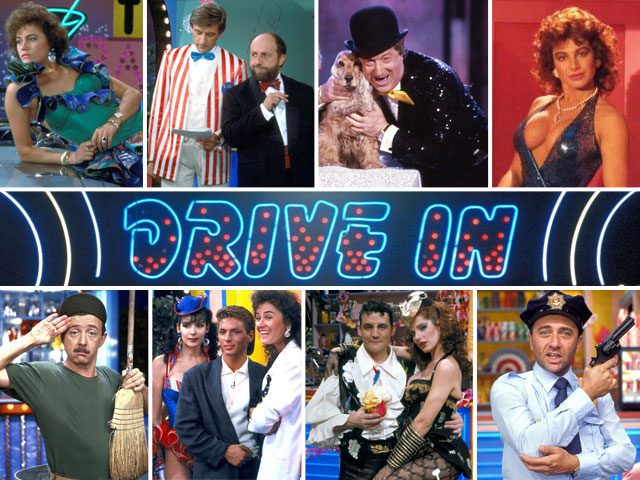

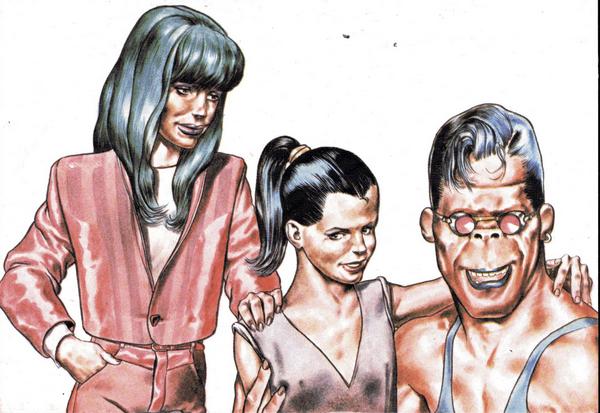

The 1980s Milan constitutes a backdrop characterized by rampant growth, competition, the first rise of Berlusconian right-wing neo-politics, the boom of high-end Italian fashion designers, mass hedonism, and the glorification of wealth. Beneath this glamorous façade lie repression, heroin, and decline. The palpable and universal police crackdown is not solely directed at those affiliated with political movements or occupation collectives but to anyone who refuses to conform to the advertising slogans of the “Milan to Drink” (Milano da Bere). To stop someone on the street, the police only need to see torn jeans, military belts, or handcuffs—or simply someone they don’t like for any reason—conversing with more than two people at the moment, which could be construed as ‘seditious assembly’.

The 1980s Milan constitutes a backdrop characterized by rampant growth, competition, the first rise of Berlusconian right-wing neo-politics, the boom of high-end Italian fashion designers, mass hedonism, and the glorification of wealth. Beneath this glamorous façade lie repression, heroin, and decline. The palpable and universal police crackdown is not solely directed at those affiliated with political movements or occupation collectives but to anyone who refuses to conform to the advertising slogans of the “Milan to Drink” (Milano da Bere). To stop someone on the street, the police only need to see torn jeans, military belts, or handcuffs—or simply someone they don’t like for any reason—conversing with more than two people at the moment, which could be construed as ‘seditious assembly’.

In general, the drive to change things that the previous Italian generation had experienced no longer exists. The confidence in conquering change has been stifled by paranoia and fear, giving rise to retrenchment, a concept that still closely concerns us today. Due to constant police checks, arrests, and detentions, living a life outside socially accepted norms, engaging in grassroots antagonistic politics, or even just walking on the streets often becomes a substantial risk. Many feel paralyzed, helpless, and therefore withdraw into their homes, living their lives predominantly in a private dimension. Sounds familiar? Tosoni and Zuccalà define this withdrawal as a “return to the private and disintegration of the forms of sociability built in the previous decade.”

Sergio di Meda, a protagonist of the first Italian goth scene, recounts, “(…) On one side, there was the ‘Milan to Drink,’ which they kept showing you all the time, with everyone having fun and going to happy hours; on the other hand, there were us, the kids who didn’t agree with that because we realized that everything was falling apart. (…) I’m an anti-fascist; I can’t stand right-wing regimes. And the impression I had, we all had, was that we were on a slope, because there was actually a kind of political and police control over everything we did. I remember saying, ‘I’m very afraid. I’m afraid that we’ll transition from a rather evident form of fascism to a hidden one, where everything will still be controlled, but with the pretense that we’re all at peace and in harmony, all democratic, free to do what we want.‘”

Joykix, a member of the group known as Kindred Creatures, says, “I meet many young people who tell me, Wow, I’ve just discovered this or that band! Lucky you, you lived through the 1980s!’ But guys, look, we were in deep shit; half of us are dead: AIDS, heroin, accidents, suicides… It wasn’t cool at all.“

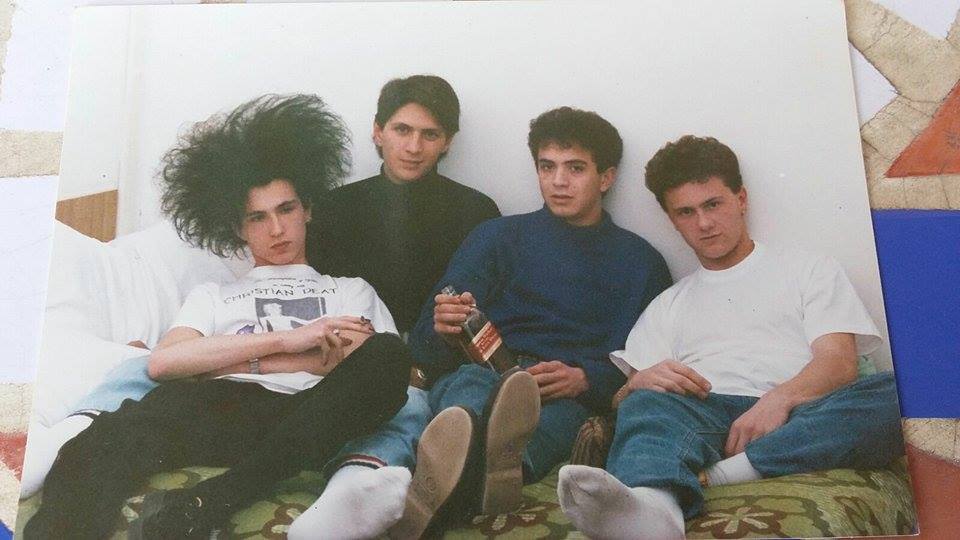

Those who became part of the subcultural movements of the early 1980s shared a common denominator: the search for new life patterns outside the imperative of work as penance and forced suffering, outside the traditional family structure, and beyond bourgeois criminalization of diversity. This is precisely the primary generative force behind subcultures: non-integration, resistance to imposed rules and codes. However, beyond being a generative force, it also poses a dangerous internal enemy—the cause of decline when the codes of rupture become rigid and imperative.

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ITALIAN PUNKS AND GOTHS

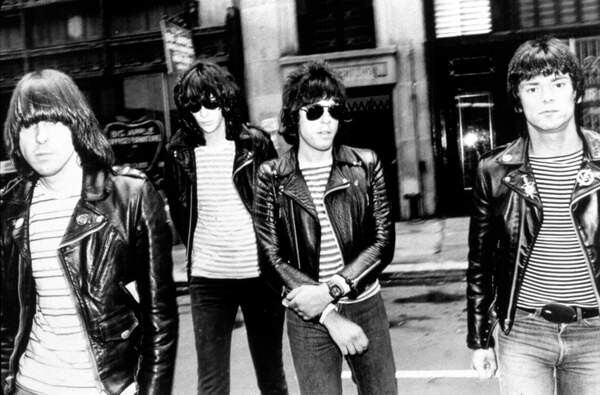

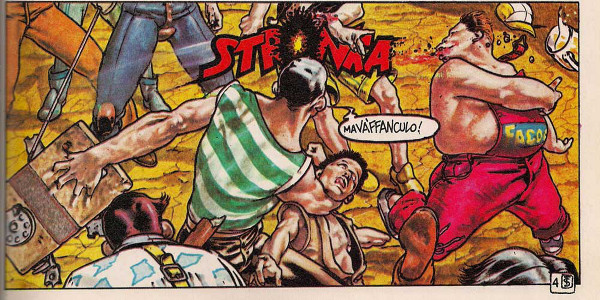

Punks and goths are closely and historically related. The first Italian punk movement emerged from the ashes and limitations of the political movements of the 1970s. There is a certain similarity in ideals but also a strong incompatibility in aesthetic and communicative codes. During demonstrations in the late 1970s and early 1980s, leftist activists often targeted the early punks, assuming they were fascists just because they wore black leather pants and jackets.

Angela Valcavi, another kindred creature, recalls that at eighteen, after being captivated by an article about London punks in the Re Nudo magazine, and after she cut her hair very short and adorned herself with safety pins, she triggered a meeting of the occupation committee at Casermetta di Baggio, followed by a political trial: “What have you got in your head? This is how fascists go around! Clarify your ideas and decide where you stand! Get your act together, because these things don’t fly here.”

Regarding the differences from the protest movements of the 1970s, Joykix reports that “The search for spaces of communication and existence was not oriented toward the hegemony and proselytism of the 1970s, on the contrary: we wanted to be few and say ‘screw you,’ have our spaces and our clubs. The term ‘club’ was never officially used, but we used it among ourselves. Anyway, it was our place where we did our things and lived separately.”

Roxie, who now curates contemporary art exhibitions, tells how the realization of their own differences led the early dark/goth scene protagonists not to isolate themselves but to try to create their own heterotopia, their own elsewhere, starting from reshaping their appearance, extending to the furnishings of their living spaces, and even finding or creating physical places in the outside world.

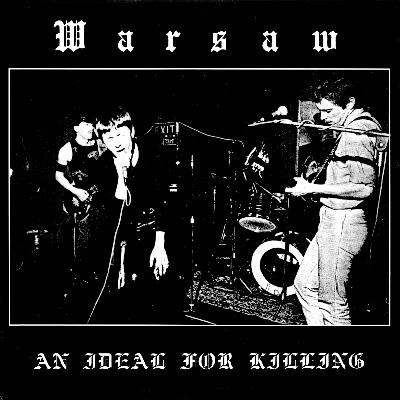

According to Sara, another protagonist of this scene, both punks and goths rely on visual shock and antagonism toward their own community. Sara asserts that the dark/goth movement is historically the child of punk: “I see a continuity; they are two sides of the same coin, and this is already true for the music alone: just think of Siouxsie, who was a Sex Pistols groupie, or Ian Curtis, whose early Warsaw had very different sounds.”

For Gp, there’s a difference in attitude stemming from the same basis of rejection: “Punk was purely angry, inclined towards destruction, sabotage, chaos, revolt; hence, it was more prone to externalization. On the other hand, goth was more internal, fascinated by decadence but also with a romantic streak.”

For Gp, there’s a difference in attitude stemming from the same basis of rejection: “Punk was purely angry, inclined towards destruction, sabotage, chaos, revolt; hence, it was more prone to externalization. On the other hand, goth was more internal, fascinated by decadence but also with a romantic streak.”

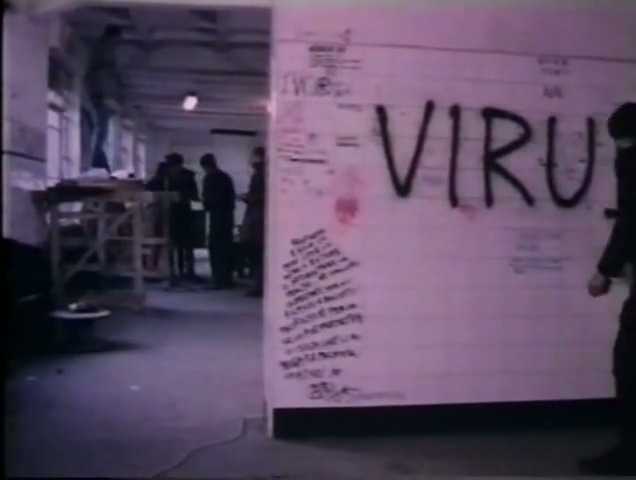

THE VIRUS

Nearly all the protagonists of the early Italian goth scene were connected to the Virus, an occupied squat that opened at Via Correggio 18 in early ’82. The Virus incubated the first, purest Italian punk movement, as described by Marco Philopat in the biographical novel “Costretti a Sanguinare” (“Forced to Bleed”). The people associated with the Virus combined outrageous aesthetics with constant political practice, always present in daily life: squatting, communal living, self-constructing and self-managing culture through organizing concerts and self-publishing, a predominantly vegetarian diet, flyering, anti-war and anti-nuclear protests. This approach led to the creation of many occupied spaces and interconnected bands within a European network, where dozens of punkzines circulated, and people flowed. According to Tosoni and Zuccalà, this way of life is marked by “radical antagonism.” The Virus was under constant siege by institutions, surviving month by month. It was finally evicted in ’84, relocating to Via Piave, where it continued to exist until 1987. The Virus was also very exclusive for reasons of self-defense.  Joykix tells, “Actually getting into the Virus crowd wasn’t easy. (…) It wasn’t easy to enter, to relate. And I have to say, I had personal difficulties as well. There were internal dynamics, subgroups: the modes of an extremely closed group, frighteningly selective. (…) If you had played even once in a commercial club, you could forget about the Virus stage.”

Joykix tells, “Actually getting into the Virus crowd wasn’t easy. (…) It wasn’t easy to enter, to relate. And I have to say, I had personal difficulties as well. There were internal dynamics, subgroups: the modes of an extremely closed group, frighteningly selective. (…) If you had played even once in a commercial club, you could forget about the Virus stage.”

Furthermore, there are differences in nature, in attitude. Sergio di Meda reported, “We didn’t fully agree with the punks: as Philopat writes in ‘Forced to Bleed,’ they looked down on us a bit because we didn’t share their same position towards politics. We weren’t actively political, so they considered us fashion-oriented, posers. (…) The problem was that we didn’t use their method, so we weren’t actively political, as they called it. We didn’t engage in attacking posters on city walls, especially those with political content, we didn’t organize concerts. Many of us did attend demonstrations, but not as a group. There was also a difference in dealing with people: they had this urge to constantly annoy people on the street, with a certain aggressiveness, in a very provocative way. On the other hand, we thought that provocation should be practiced visually, creating confusion with our way of presenting ourselves.“

Despite these differences, there are many affinities, fundamental principles that many present-day members of the dark scene seem to have forgotten. Dave reports, “Yet I started out with punk by necessity; the two scenes often overlapped. We shared a fundamental thing: the will not to conform to the fashion of the era, to the paninaro Italian subculture of designer clothing, to displaying wealth, to right-wing political ideology, to machismo.“

SO THIS DEFINITION POPPED UP

From the alien nature of some elements, irreducible to the environment of the Virus punks, the first definition of goth in Italy emerges. Roxie recounts, “At the Virus, someone started to play with goth codes, but not everyone liked it: in fact, I had the feeling of not being well-received by the occupants. When I got to know them, their stance seemed interesting, but compared to me, to how I was, I found it too extreme: I would never have gone to an occupied house without my room and my things! (…) Some would say to me, ‘You’re not punk, you’re a kindred creature,’ an expression used by Helter Skelter folks to describe people with similar attitudes, but who didn’t fully identify with the more politically charged punk scene.“

_End of the First Part of the Article about the Kindred Creatures_

The next chapter of this article will be about the psychogeography of the first Italian goth scene, its venues, rituals, and gigs. But the very next article will be the first part of our history of the color black. Stay tuned for more waves of the black tide!

Bibliography

If you enjoyed this article and are interested in delving deeper into the topic, you can find some bibliography in the following links. If you appreciate our content and would like to support the activities of our site, you can make purchases through these links, not necessarily limited to books listed in the bibliography but any kind of item. To do so, simply access the link and then fill your cart. Thanks to everyone!

Simone Tosoni, Emanuela Zuccalà, Italian Goth Subculture. Kindred Creatures and Other Dark Enactments 1982-1991

Marco Philopat, Costretti a sanguinare. Shake Edizioni. 1997

On the Virus

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_wWI1irCgOc

http://www.ecn.org/leoncavallo/storic/helt.htm

Images credits

Thanks to Simone Tosoni, Sergio di Meda, Joykix, Angela Valcavi, and Donatella Bartolomei for the additional info and the pictures.