1 in 10 seven- to eight-year-old child hears voices which aren’t really there.

According to a Study by the University Medical Centre, Groningen, Netherlands

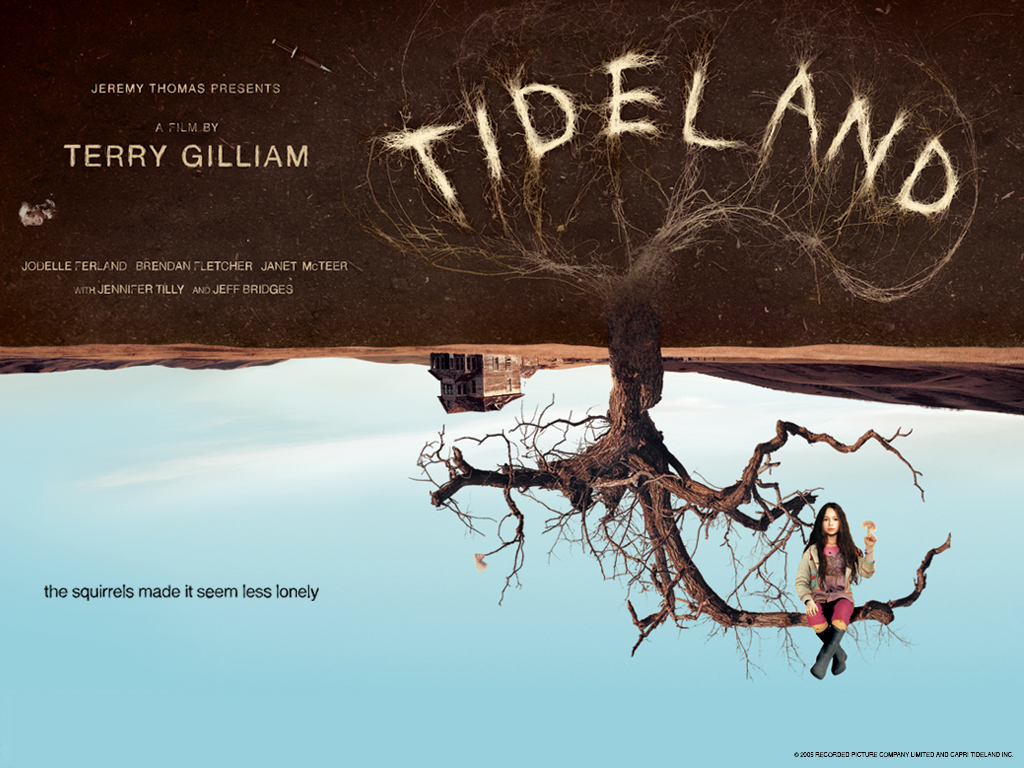

Jeliza Rose, an eight-year-old girl, has got a father who dreams of the Vikings’ land and a mother who looks like Courtney Love, and she helps them both to shoot up heroin.

Jeliza Rose, an eight-year-old girl, has got a father who dreams of the Vikings’ land and a mother who looks like Courtney Love, and she helps them both to shoot up heroin.  At a certain point, Mum lifts off to her world made of endless chocolate bars and of the most gorgeous high-heeled shoes, and Dad soon follows her, going on a no-return vacation. Jeliza Rose is left alone, in a house surrounded by wheat fields, in company with four doll heads which sooner or later should stop talking. Necrophiliac witches thinking they are Jesus Christ, hydrocephalic freaks turning into princes thanks to the kiss of love, happy families with a stuffed corpse sitting at head of the table: the creepy and harrowing world of Tideland, directed by Terry Gilliam (2005), shows perfectly the extremisms and the magic powers of childhood, the period when the slash which separates reality from fiction is highly unstable.

At a certain point, Mum lifts off to her world made of endless chocolate bars and of the most gorgeous high-heeled shoes, and Dad soon follows her, going on a no-return vacation. Jeliza Rose is left alone, in a house surrounded by wheat fields, in company with four doll heads which sooner or later should stop talking. Necrophiliac witches thinking they are Jesus Christ, hydrocephalic freaks turning into princes thanks to the kiss of love, happy families with a stuffed corpse sitting at head of the table: the creepy and harrowing world of Tideland, directed by Terry Gilliam (2005), shows perfectly the extremisms and the magic powers of childhood, the period when the slash which separates reality from fiction is highly unstable.

A child lives in a pre-logical universe, expanded into all dimensions, rich with hidden meanings. In the child’s perception, everything is so amplified that it synchronically flows into distortion and revelation. The child’s communication codes proceed by symbols, and childhood is the age of the divine archetypes. The king, the queen, the princess, the wicked witch, the orphan, the seeker, the mentor, the shape-shifter, the shadow: those same figures which, from the very depths, will pull the strings of the future adult’s psyche.

A child lives in a pre-logical universe, expanded into all dimensions, rich with hidden meanings. In the child’s perception, everything is so amplified that it synchronically flows into distortion and revelation. The child’s communication codes proceed by symbols, and childhood is the age of the divine archetypes. The king, the queen, the princess, the wicked witch, the orphan, the seeker, the mentor, the shape-shifter, the shadow: those same figures which, from the very depths, will pull the strings of the future adult’s psyche.

Fairy tales are the first and most dazzling empire of archetypes. They always tell about those rituals of passage and transformation which develop out of a crisis. Beyond the superficial polarization between the bad and the good ones, the fairy tale is never Manichaean: good and evil need each other. And evil is always seductive. Classical logic is banished from the child’s cognitive system, for him/her the principle of non-contradiction is ordinary approximation, mere grossness. What really counts is the insight, the Force of Star Wars, the sacred aloofness from the horror. Children see everything, even the things which don’t exist.

Fairy tales are the first and most dazzling empire of archetypes. They always tell about those rituals of passage and transformation which develop out of a crisis. Beyond the superficial polarization between the bad and the good ones, the fairy tale is never Manichaean: good and evil need each other. And evil is always seductive. Classical logic is banished from the child’s cognitive system, for him/her the principle of non-contradiction is ordinary approximation, mere grossness. What really counts is the insight, the Force of Star Wars, the sacred aloofness from the horror. Children see everything, even the things which don’t exist.  They can allow themselves any excess, they are the master of the game and they still have lawfulness to insanity. Therefore, the child’s modalities of existence are pretty close to those of art-making.

They can allow themselves any excess, they are the master of the game and they still have lawfulness to insanity. Therefore, the child’s modalities of existence are pretty close to those of art-making.

There is a particular art movement, born in America in the Seventies, from spurious hands belonging to the world of comics, cartoons and graphics. It spread worldwide in the Ninetines. This movement is known as Lowbrow Art or Pop Surrealism. There is an explicit dimension of everlasting childhood in it: the style-manners of cartoons, of fairy tales and of the gadgets for children combine with uncanny contents. And, finally, they do it by the light of the sun. Pop Surrealism stages the Garden of Consumeristic Delights, conceived by and for that generation of children accustomed to ask for things and to be always satisfied.  All the low-browers are fetishist, they collect objects: daguerreotypes, medical tools, animals stuffed with straw, ugly dolls, underground comics, piratical fetishes, vintage decorations for Halloween, skulls of hominids. Goods never say no, they satisfy any wish, you just have to buy them. Indeed, consumerism originates from a childish impulse, the whim to be satisfied.

All the low-browers are fetishist, they collect objects: daguerreotypes, medical tools, animals stuffed with straw, ugly dolls, underground comics, piratical fetishes, vintage decorations for Halloween, skulls of hominids. Goods never say no, they satisfy any wish, you just have to buy them. Indeed, consumerism originates from a childish impulse, the whim to be satisfied.

Children are so able to distinguish between natural and supernatural things that their intuition leads us to think about a sensitive religious period: the first period of life seems linked with God, as physical development of the body is strictly dependent on the laws of nature which are transforming it.

Maria Montessori

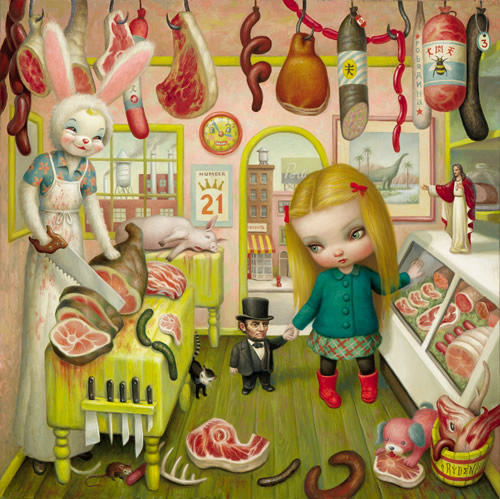

Mark Ryden mixes meat and flesh, toys and religious emblems, because the religious sphere is tangent to the magical sphere, typical of childhood. All the protagonists of his paintings are children, the oldest ones are just at the edge of adolescence. With them there are little pastel toys, polka-dot giraffes, smiling balloons, pink plush bunnies, all mixed with cut-off ear lobes, prehistoric echinoderms, skulls, foetuses, Masonic symbols and statuettes of Jesus Christ which come to life. Tiny toys jumble up with fragments of bodies, with dead and torn off things, ready to be sold on the butcher’s counter.  Ryden paints the cryptic rituals which lead to adulthood, when the craving for toys will change into the craving for flesh and pieces of meat, to torn to pieces for predatory voraciousness or sexual appetite.

Ryden paints the cryptic rituals which lead to adulthood, when the craving for toys will change into the craving for flesh and pieces of meat, to torn to pieces for predatory voraciousness or sexual appetite.

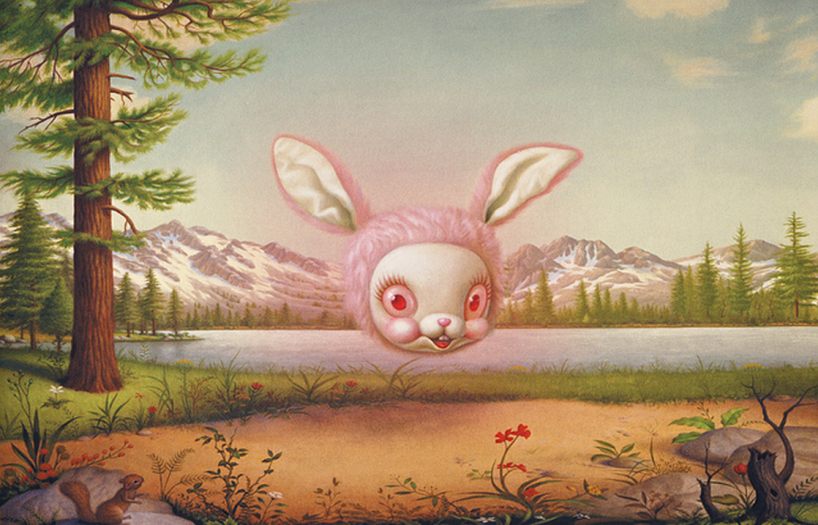

Marion Peck, his partner, associates two categories of alterity, children and animals, often depicting them together.

In both cases, Peck exaggerates the roundish features of puppies, that are the characteristics which should inspire tenderness and protection instinct in the adult members of the pack. She over-emphasizes these features until she gets repulsive and gloomy caricatures.

In both cases, Peck exaggerates the roundish features of puppies, that are the characteristics which should inspire tenderness and protection instinct in the adult members of the pack. She over-emphasizes these features until she gets repulsive and gloomy caricatures.

I used to be the kind of child whom my mother told me never to play with.

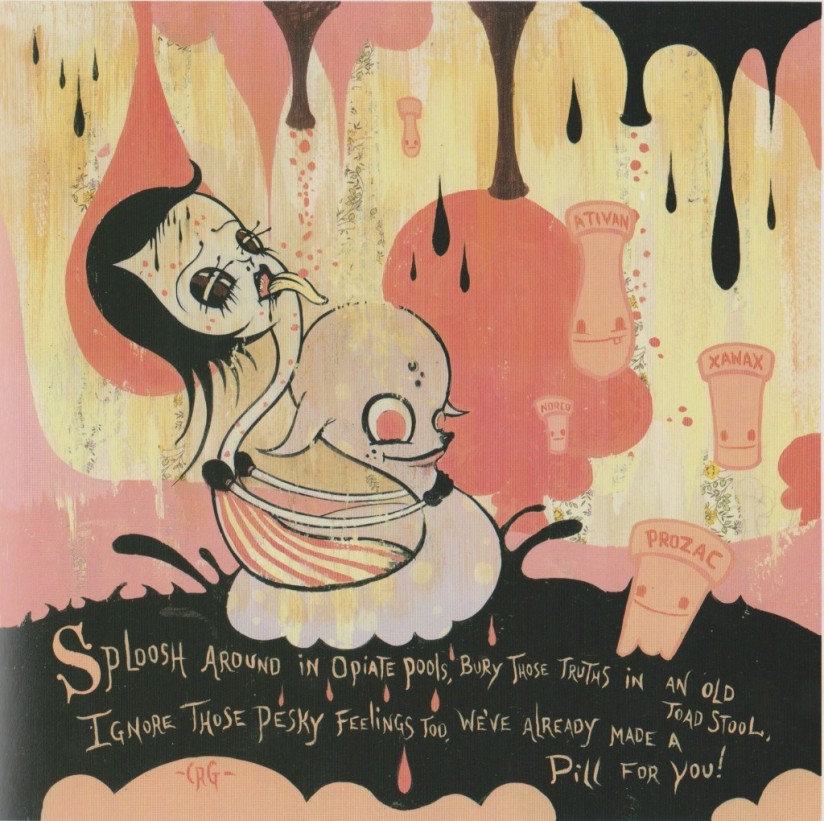

Little dolls with long and thin limbs like Olive-Oil, with black lipstick and striped tights in Tim Burton’s style. They have big heads like Bettie Boop, coy little curls, but their big eyes are dizzy and misted. In a patchwork of flowery textures and candy pink balloons, small happy missiles rain down with Xanax, Prozac and Halcion written on them.

Little dolls with long and thin limbs like Olive-Oil, with black lipstick and striped tights in Tim Burton’s style. They have big heads like Bettie Boop, coy little curls, but their big eyes are dizzy and misted. In a patchwork of flowery textures and candy pink balloons, small happy missiles rain down with Xanax, Prozac and Halcion written on them.  Nursery rhymes constitute the ironic and bitter comment on the Pharmacuticools by Camille Rose Garcia: “Sploosh around in opiate pools, bury those truths in an old toadstool, ignore those pesky feelings too, we’ve already made a pill for you!”. The artist reflects upon pharmaceutical addiction as a way to be a child forever. On her settings, taken from the dark side of the early Toontown, drug turns into a good parental figure, who satisfies every wish and staunches every pain.

Nursery rhymes constitute the ironic and bitter comment on the Pharmacuticools by Camille Rose Garcia: “Sploosh around in opiate pools, bury those truths in an old toadstool, ignore those pesky feelings too, we’ve already made a pill for you!”. The artist reflects upon pharmaceutical addiction as a way to be a child forever. On her settings, taken from the dark side of the early Toontown, drug turns into a good parental figure, who satisfies every wish and staunches every pain.

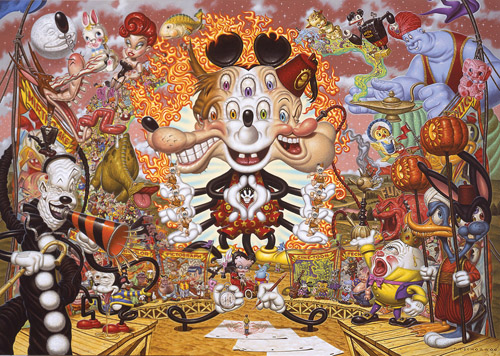

In The Spectre of Cartoon Appeal, Todd Schorr depicts a mutant Trimurti with the heads of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse, E.C. Segar’s Popeye and Avery’s Wolfie, surrounded by a ramshackle parade of their acolytes: an apotheosis of cartoons and American icons for children. Some of them are foaming at their mouth, other ones have a scary or weird look. Everything looks as if it is going to explode: the paroxysm of fun runs the risk to turn into a bad trip.

We can say anything about children, except that they are innocent. I can just quote dear old Professor Freud and his definition of the child as a “perverse polymorph” (…) After all, Altemberg had already told of a cerulean four-year-old girl, with a seraphic and almost offensive grace: she was watching a stage performance of Snow White with her parents, and she was told that a roe deer would be killed in the wood at the place of her heroin, and she replied: “Oh, if I cannot see when Snow White is killed, will the roe deer be killed at least in front of our eyes?”. Thunderous delicacy.

Giorgio Manganelli, Il Compagno segreto – “Lunario letterario” – No. 5, October 2003

Ray Caesar, before undertaking the art career, spent over ten years working in the Children Hospital in Toronto. His universe is cruel and fragile, crowded with mannequins frozen on the threshold between childhood and puberty. They are mostly very young, but never completely “children”, they always have a bit of naughtiness. The marmalade thief of Ecstasy got her seashell colour robe dirty, a with red-blood stain exactly on her lap. There is a blonde little princess inside a rococo room, who plays strange games with her doll Precious.

Ray Caesar, before undertaking the art career, spent over ten years working in the Children Hospital in Toronto. His universe is cruel and fragile, crowded with mannequins frozen on the threshold between childhood and puberty. They are mostly very young, but never completely “children”, they always have a bit of naughtiness. The marmalade thief of Ecstasy got her seashell colour robe dirty, a with red-blood stain exactly on her lap. There is a blonde little princess inside a rococo room, who plays strange games with her doll Precious.  The androgynous protagonist of Harvest loves playing dangerous games instead, and you better get off her way.

The androgynous protagonist of Harvest loves playing dangerous games instead, and you better get off her way.  The twins Castor and Pollux smoke the pipe inside their Victorian baby carriage, sporting sailor tattoos and two strange vermiform outgrowths.

The twins Castor and Pollux smoke the pipe inside their Victorian baby carriage, sporting sailor tattoos and two strange vermiform outgrowths.

Caesar shows how childhood is not an angelic and innocent age, as the moralistic preceptors and the commercials about happy families want to make us believe. Like every age of human beings, also childhood has not to be immune from cruelty, sexuality and awareness. All the main artists of Pop Surrealism agree on demonstrate how childhood is the other age par excellence, and how such dimension of alterity functions as a mirror, to reflect what we really are.

All the main artists of Pop Surrealism agree on demonstrate how childhood is the other age par excellence, and how such dimension of alterity functions as a mirror, to reflect what we really are.

Published on Drome Magazine 18, the Childhood Issue, spring 2010.